I suppose it’s possible to call this camera the epitome of film point and shoots; it was, after all, quite possibly the Volkswagen Beetle of its generation. Made in huge numbers (3.8 million for this model alone, 10 million of all Mju variants), not especially expensive, but by all accounts incredibly reliable and delivering consistently excellent results. I certainly remember lusting after one while growing up, but through some strange turn of events landed up buying a rather useless Fuji 1010ix APS camera instead, which I still regret to this day. Thanks to some blind luck and the quick actions of a friend, I managed to eventually get my hands on one – new in box, for not much more than a brick of film.

Just updated the Olympus E-P5 review…

I’ve had the opportunity to shoot with a final production Olympus E-P5 for the last week or so, which means I’ve been able to update the image quality section of the review. You can find the whole thing (including the update, of course) here. MT

Thanks to the folks at Olympus Malaysia for making it happen.

Photoessay: New York street cinematics

Possessiveness of taxis is a New York thing

I found the people and streets of New York to be eminently suited to a bit of cinematic street photography. Perhaps it’s the fact that so many movies have already been filmed in New York, or it’s the quality of light filtering between and reflecting off buildings, or it’s the various diverse characters that live in the city. These are little moments, vignettes and slices-of-life; I don’t want to use the word ‘stolen’, but it does sometimes feel like one is peering into a pre-coreographed scene and simply borrowing a frame. I sincerely apologise in advance for having some fun with the captions.

Review: The OIympus PEN E-P5 (updated)

Not so long ago, Olympus updated both the E-PL series (E-PL5 reviewed here) and the E-PM series with the OM-D’s sensor and other trickle-down technology. Thus it only made sense that it was also about high time for the E-P3 to be refreshed, too. They’ve taken a bit longer over this one; in fact, the new E-P5 has so much of the OM-D’s technology (and a few other things) that picking one over the other is no longer such an easy decision.

Updated 18 June: I’ve had the chance to shoot with a final production E-P5 and VF-4, and have added conclusions on image quality below. The camera looks and feels physically identical to the earlier prototype I tested. In the intervening time, an update to Adobe Camera Raw has also been released that natively supports the E-P5, so I’ve had the ability to evaluate RAW file quality on a comparable basis to the OM-D.

Sony and Olympus: what does it mean?

Following the accounting scandal that saw former CEO Michael Woodford ousted, Olympus’ coffers were looking decidedly empty; at that point, many potential suitors were rumoured. It turned out that Sony was the one whose offer was accepted. In a share transfer and cash deal – completed about a month ago – Sony pumped US$645 million into the company, to hold a total of 11.5%. What’s more interesting is that on most of the major business sites, this wasn’t reported as a transaction to invest in the cameramaker; rather, Olympus was frequently referred to as a ‘world leader in medical imaging’.

Although photographers know and love Olympus as the manufacturer of various quirky cameras and small systems, the truth is that margins in the medical industry – anything with ‘surgical’ or ‘medical’ in its name means an extra couple of zeroes on the end of the price tag – are much, much higher than the camera business. Like Nikon, it’s been making a good chunk of its income from something other than cameras for a long time. (I don’t know how much it makes from dictaphones these days, though.)

I’m going to take off my photographer hat now and wear my analyst/ M&A/ consultant one, for a bit of change of pace. Let’s put the pieces together.

Lens review: The Olympus ZD 12/2

Although this lens is not new – in fact, it was announced back in 2011 with the second-generation E-P3, E-PL3 and E-PM1 (full review here) – it still remains ostensibly the best fast wide option for Micro Four Thirds users. (It was also recently re-released as a limited edition all-black version, which now includes the lens hood as part of the kit.) In fact, there’s been remarkably little competition in this arena – just a manual focus offering or two from SLR Magic, and the upcoming (and stratospherically priced) Schneider 14/2.0. Panasonic has the 7-14/4, and the 14/2.5; the latter which is perhaps the 12/2’s closest competition.

My initial experience with this lens and its optics on the E-P3 and E-PM1 were enough to convince me that Micro Four Thirds had come of age, and would make a worthwhile compact system without major compromises for the majority of situations in which I’d want to use a compact system camera. This impression held, wavered, and changed again – to be honest, until the last Tokyo workshop, I hadn’t had much of an opportunity to use the 12/2 on the OM-D (full review here) for a serious evaluation. The last time I used the lens on the OM-D was also the first time I’d taken out the camera for a serious bout of shooting, and definitely wasn’t a good way to benchmark performance of either camera or lens – simply too many variables and unknowns were in play here.

The lens is one of the Olympus Super High Grade line, impeccably built and finished with all-metal construction, and one unique feature (for a Micro Four Thirds Lens) – the focusing ring clutch. Sliding the focusing ring backwards a notch puts the lens in manual focus mode, and also reveals a focus distance scale: unlike every other lens in the system, the 12/2 has hard stops at each end of the range. Together with the depth of field scales, the lens should theoretically be the ideal tool for street photography – fast, wide, zone-focusable, and with more depth of field for a given aperture and field of view than its 35mm equivalent.

In AF mode (left) and scale-focus MF mode (right)

Except, this isn’t quite the case. Sadly, the clutched focus system isn’t really mechanically linked to the position of the lens elements; it too is a fly-by-wire simulation – albeit a very good one, with the right amount of tactile feedback and everything. The problem is to do with the resolution of the distance scale/ mechanism: there aren’t enough divisions.

Reflections, Tokyo. OM-D, ZD 12/2 from a moving train

It seems that there are perhaps five or six discrete distances to which the focusing group moves, instead of a continuum. The only thing that could cause this is if Olympus used a form of rheostat in the construction of the the focusing ring/ clutch. Although 12mm is a very wide actual focal length with plenty of depth of field for a given aperture, f2 is fast enough that more critical control over your focus point is required. Sadly, though the idea of the ring is a good one, the execution makes it of marginal utility for the photographer in the real world – unless you are willing to use a small aperture – f4-5.6 or smaller – to use depth of field to cover the lack of manual focus precision.

Diagonals, Shibuya. OM-D, ZD 12/2

Curiously, this is most definitely not the case for either manual focus with the ring in the AF position (i.e. selecting manual focus on the camera body) or when using autofocus. Here, the lens is precise, moves in as many infinitesimally incremental steps as one could desire, and has no trouble finding critical focus. While on the subject of focusing, it’s probably a good time to talk about autofocus performance. Like all of Olympus’ other MSC designs, the 12/2 is an extremely snappy lens – even more so on any of the recent bodies. I haven’t experienced any gross focus misses, but it’s worth noting that some care is required at f2 – the plane of focus isn’t quite as deep as you’d think.

Taxi rush, Shinjuku. OM-D, ZD 12/2

The lens is not weather sealed or gasketed, and once again, Olympus has decided not to include a hood – this is excusable for a $250 economy kit item, but not on a $800 premium lens. It just smells too much like penny pinching. Perhaps it’s just as well, because the optional hood is rather cumbersome; it increases the bulk and visual size of the lens hugely, requires a thumb screw to attach, can rotate freely and requires a different cap – why can’t they just use a bayonet hood? Zeiss lenses are a great example of how bayonet hood mounts should be constructed.

Shadows, Otemachi. OM-D, ZD 12/2

Over a good year of use with this lens on the E-PM1 and OM-D, those are my only two complaints: the inaccuracy of the pseudo-manual focus clutch, and the continued minor farce of the lens hood. If you read this carefully, it means that I don’t have any major criticisms of the optics.

The 12/2 uses a rather exotic optical design with 11 elements in 8 groups; one of these is aspherical, one is made of ED glass, and another two of exotic Super HR and DSA glasses. It’s a non-symmetric, telecentric design whose optical formula honestly doesn’t look familiar to me – the closest thing I can think of are the Zeiss Distagons, insofar as they use several extremely dome convex front elements and a rear telephoto group. The lens also employs Olympus’ ZERO coating to minimize flare and maximize contrast and transmission.

Let’s get the most popular question out of the way first: yes, it’s sharp. Bitingly so, at all apertures, across the entire frame in all but the most extreme corners. There appears to be a small amount of field curvature, but nothing overly serious; enough that for optimal sharpness you’ll want to move the focus point over your subject rather than using center-focus-and-recompose, though. The lens has a slightly odd MTF chart that is indicative of a significant dropoff in microcontrast about halfway to the edges; I don’t see this in practical use, which suggests that the field curvature is probably responsible – and more complex than a merely spherical surface. In the real world: sharpness will not be an issue.

Fuji TV building, Odaiba. OM-D, ZD 12/2

Though some of you might think that a little nice bokeh might be obtainable from the 12/2, you’d be mistaken; you have to be very close indeed to throw anything significantly out of focus. Fortunately, the lens focuses down to 0.2m, so this is actually possible. If you have enough distance between subject and background, then bokeh is actually fairly pleasant; however, if there isn’t a lot of distance, and the subject is a bit farther away from the camera, nothing really gets out of focus enough to begin with – in fact, you have to be a bit careful of double images in the out of focus areas. There’s a bit of spherochromatism, too.

Although the lens in general well corrected, you do get the feeling that it’s on the extreme edges of what was possible with the design constraints put upon the optical designers: there’s visible CA against high contrast subjects, especially in the corners where you can get up to 2 pixels’ worth; there’s also very noticeable distortion. Fortunately, it’s fairly simple in nature – barrel with no sombrero/ moustache – and is easily correctable in ACR. Flare exists but the ZERO coating does a good job of keeping it to a minimum – even without the hood. Stopping down to f4 on the OM-D makes everything but the distortion go away, leaving you with an excellent optic. It doesn’t quite have the transparency of the 75/1.8 or 60/2.8 Macro, but it’s fairly close if used stopped down. It is definitely the best wide option for M4/3 users at the moment. One interesting use of the lens is for handheld long exposure photography – due to the short focal length and excellent stabilizer in the OM-D, shutter speeds of anywhere down to 1/2s (consistently) or 1s (occasionally) with critically sharp results are possible, making for some interesting photographic opportunities.

As always, I suppose the litmus test for a lens is if you’d buy it a second time – I think the answer for me would be a qualified yes. I have since had the chance to shoot with the Panasonic 14/2.5; thought I prefer the 28mm field of view over 24mm, and believe that M4/3 lenses should be a compact as possible to play to the other strengths of the system, I would still pick the 12/2 as the optics are better – they simply render in a more three-dimensional way due to better microcontrast, as well as better edge sharpness. Interestingly, the Panasonic 12-35/2.8 runs it very close at f2.8; however, the T stop of that lens is about 1/3-1/2 stop slower too, for a given physical aperture. What qualifies my opinion is the upcoming Schneider 14/2; it remains to be seen if it performs as well as its price suggests it should. In the meantime, the best way to judge the 12/2 is on its pictorial results – construction, expensive accessories and the imprecise focus clutch are just distractions. And on that basis alone, I think the lens deserves a place in a serious M4/3 shooter’s bag. MT

The Olympus M.Zuiko Digital 12/2 is available here from B&H and Amazon.

____________

Visit our Teaching Store to up your photographic game – including Photoshop Workflow DVDs and customized Email School of Photography; or go mobile with the Photography Compendium for iPad. You can also get your gear from B&H and Amazon. Prices are the same as normal, however a small portion of your purchase value is referred back to me. Thanks!

Don’t forget to like us on Facebook and join the reader Flickr group!

Images and content copyright Ming Thein | mingthein.com 2012 onwards. All rights reserved

Comparative lens review: The Olympus M. Zuiko Digital 17/1.8

Advance note: Images in this review were shot with an Olympus OM-D and the ZD 17/1.8 unless marked otherwise. Please go by the commentary rather than the reduced crops; I am looking at uncompressed RAW files on a calibrated monitor, not a websize JPEG. The review was completed with a final pre-production prototype lens. I’m told that image quality and build are representative of the finished product.

With (once again) poorly designed and optional lens hood. At this price…shame on you, Olympus.

With (once again) poorly designed and optional lens hood. At this price…shame on you, Olympus.

One of the first lenses released for the fledgling Micro Four Thirds system was the 17/2.8 – equivalent to 34mm in full-frame talk, and the staple walk-around lens for most photographers. I’ve personally never been a fan of this focal length – it simply doesn’t fit with the way I see – so I tried it once on the first E-P1, and never paid it much attention since. That lens was a simple 6/4 design with a single aspherical element at the rear, and notorious for managing to pack many undesirable qualities into a single lens at once – it was slow to focus, suffered from serious lateral chromatic aberration at the edges at pretty much all apertures, and was extremely noisy while hunting to boot.

Its sole redeeming graces were that it was sharp in the center of the frame, and very small. Most photographers ditched that lens for the Panasonic 20/1.7, which was a little longer, not much bigger, but over a stop faster and optically comparable. That lens made its way into my bag while I was shooting with the E-PM1 Pen Mini, turning the camera into a small and pocketable companion.

Olympus has been on a bit of a roll lately with its Micro Four Thirds lenses – first the 12/2, followed by the 45/1.8, then the 75/1.8 and 60/2.8 – the latter two of which are amongst the best lenses I’ve used for any system, period; the new M.Zuiko Digital 17mm f1.8 (hereafter known as the 17/1.8) is the latest to follow in this vein.

The lens’ construction is closer to the 75 and 12mm lenses than the 45 and 60, which is to say it follows the High Grade requirements of being all-metal in construction (champagne-colored anodized aluminum) and having the ZERO optical coating. It has the same pleasant tactility and solidity as the 75 and 12mm lenses; there’s no plastic to be seen anywhere here. Unfortunately the lens is not weather sealed and has no visible gaskets, and once again, has an optional (and expensive) lens hood that makes it very difficult to remove the lens cap. Like the 12/2, the full-time manual focus ring override clutch activated by pulling the focusing ring backwards towards the camera. In this position, the ring exposes the distance scale which works in conjunction with the depth of field scale engraved on the static outer flange, and has fixed end stops at minimum focus distance and infinity. Unlike the 12/2, the possible distances are no longer fixed to several discrete ranges – pulling back on the ring and turning it slowly through its range of travel, you can see via the LCD image that the focus distance changes continuously. If there are discrete steps, they’re very small ones. This is great news – whilst the idea was a good one for reactive documentary photography, its implementation on the 12mm made it fairly useless in practice.

Needless to say, autofocus speed is on par with all of the current generation of Olympus lenses – very, very fast indeed. It’s much faster than the 17/2.8 and Panasonic 20/1.7 – about the same as the 12/2, and slightly faster than the 45/1.8 (which is to be expected because that lens has a longer focus travel as required by its focal length). I did experience one or two issues with precision at longer distances wide open though – admittedly an unlikely usage scenario – the lens tended to lock at about 6-10m distance instead of infinity; as a consequence, images were borderline sharp but nowhere near what the lens can produce if focused properly. The 17/1.8 focuses down to a minimum of 25cm, which in practice means covering a 15x20cm object or thereabouts. It’s slightly less than the 20cm minimum of the 17/2.8, but curiously the real focal length of the 17/1.8 seems to be a bit longer, which lands up evening things out in the end. Close up performance wide open is not its strength; there’s a distinct loss of microcontrast that robs resolving power, that only starts to come back at f2.8 and smaller – this isn’t entirely surprising as the lens lacks any floating elements. In this area, I’d say it’s on par with the 20/1.7, and slightly worse than the 17/2.8.

Optical formulae. 17/1.8 at left, 17/2.8 at right.

The 17/1.8 is a much more complex lens than the 17/2.8 that preceded it. Firstly, focusing takes place entirely within the lens, in order to keep things fast and silent; the entire optical assembly no longer moves. It’s a complex 9/6 design that appears to have been done entirely by computer; I don’t recognize the optical formula at all. Olympus have spared no expense here – two aspherical elements, one HR element, and one DSA (double super aspherical) element go into the mix. Both front and back surfaces are flat, which presumably has a positive effect on flare; I certainly didn’t see any during my test images, which included several deliberately backlit shots and point sources within the frame. No doubt the ZERO coating helps, too.

MTF charts. 17/1.8 top, 17/2.8 bottom. Image from Olympus Malaysia

On the basis of the MTF charts alone, both lenses should perform similarly in the center, with excellent overall sharpness and contrast, and middling to good microcontrast. Towards the outer portions of the frame, the 17/2.8 drops in fine resolving power, and loses it in the corners. This is not because the lens isn’t sharp: huge amounts of chromatic aberration mixed in with field curvature rob resolving power. The 17/1.8, on the other hand, maintains its overall resolving power out much further towards the edges – remember this is at f1.8, against the 17/2.8 at f2.8 – with a dropoff only in the extreme corners. The complex wave form of the 60 lp/mm lines suggests that it’s probably due to some very odd field curvature, probably as a result of the complex optical design. The 17/2.8, on the other hand, has a simpler, less corrected, design, with resulting first- and second- order uncorrected field curvature. Geometric distortion is very low, however, and requires almost no correction in Photoshop.

In a very quiet back alley somewhere, waiting for the person to complete the shot that never arrived.

In practice, what this means for sharpness is that the 17/2.8 was good in the center, but terrible in the corners and lacking punch and transparency. From what I’ve seen, the 17/1.8 markedly improves on this in practical situations; the sweet spot extends much farther out from the centre even wide open at f1.8, and by f4 performance is uniformly excellent across the entire frame – in some ways, reminiscent of the behaviour of the 12/2. Note that this is a lens which performs best if you place the focus point over the intended subject; focus-with-the-center-point-and-recompose is not going to yield optimum results due to the nature of the 17/1.8’s field curvature profile.

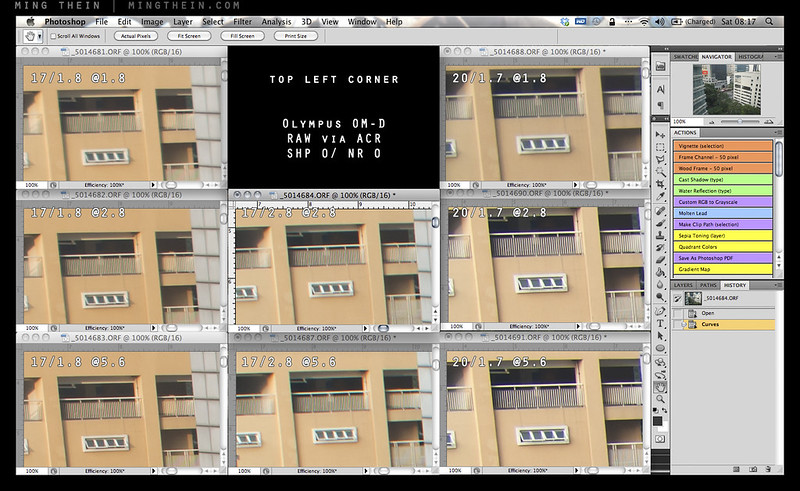

3-way comparison of center resolution. 100% version here. The 20/1.7 has the highest overall scene contrast, but the 17/1.8 wins out in microcontrast and reproduction of fine detail structures – personally, I prefer this as it gives me more latitude for processing before the shadows and highlights block up. The 17/2.8 is in the middle for macro contrast and on par with the 20/1.7 for microcontrast.

Top right. 100% version here. Note purple fringing on the 20/1.7 shots, even at 5.6. That portion of the building is not overexposed according to the histogram. The two Olympus lenses exhibit notable CA, with the 17/2.8 being the worst offender.

Top left. 100% version here. The 20/1.7 is oddly free of both CA and purple fringing in this corner; in fact, the performance here doesn’t really match the other corners – chalk it down to sample variation. This is the 17/1.8’s worst corner.

Bottom right. 100% version here. We’re now seeing CA from all three lenses, with the 17/2.8 once again faring the worst. The 17/1.8 is slightly better than the 20/1.7. Interestingly, not much changes even when you stop down.

What will affect resolution (and perceived acuity) far more is lateral chromatic aberration. The 17/2.8 was notorious for this, and to be honest, the 17/1.8 shows a notable improvement over its predecessor, but CA is still present to f4. Both lenses have visible longitudinal chromatic aberration and spherochromatism that show up as fringes in the bokeh; the new lens is slightly better but still not perfect. This does not affect microcontrast as much as you would expect as the longitudinal CA occurs only in out of focus areas, which are devoid of microcontrast and fine detail structures anyway. In the in-focus areas, microcontrast delivered by the 17/1.8 is already good wide open, improving slightly to peak at f4. The 17/1.8 has about the same global contrast as the 17/2.8 at comparable apertures, but slightly better microcontrast and the ability to render more subtle tonal gradations.

Whole test scene. Yes, that’s a Lego chess set. A custom one: goons vs. the village people.

Bokeh, LoCA and spherochromatism, #1. 100% version here. I’d say the 20/1.7 looks best here, but it’s very nearly a tie with the 17/1.8.

Both lenses have surprisingly consistent color rendition despite their vastly different construction and coatings; that is to say, neutral to slightly warm, with decent (but still plausibly natural) saturation. Where they differ is in transmission: (see this article for the difference between T stops and f stops) it’s clear that the coatings used in the new lens endow it with significantly better lower internal reflection properties than the older lens. Despite having more elements and air-glass surfaces, the 17/1.8 meters with a shutter speed that’s about 1/3-1/2 stop faster than the old lens for a given fixed aperture and histogram (luminance) output. This is a useful gain in practical situations; it’s not quite see-in-the-dark territory, but good transmission characteristics combined with its relatively short focal length and the excellent stabilization system on the OM-D mean that its useability envelope is very wide indeed. Vignetting is also fairly negligible too, even wide open.

Bokeh, LoCA and shperochromatism, #2. 100% version here. No prizes for guessing the 20/1.7 has the best rendition since it also has the longest focal length; this portion is a bit of a lopsided comparison.

The 17/1.8 renders out-of-focus areas with a rounded softness and lack of hard/ bright edges or double images, even against complex background textures. Whist you’re never going to get a large amount of defocus to your backgrounds with a real focal length of 17mm (that’s a property of the focal length) unless you get very close to your subject with a simultaneously distant background, what you do get with the 17/1.8 is very pleasant. I actually think the 17/1.8 delivers close to the right amount of bokeh for most situations at relatively near distance; enough to separate the subject but not so much as to completely abstract out backgrounds.

Throughout this review, I’ve talked a lot about its predecessor, the 17/2.8; the other dark horse sitting in the corner is the Panasonic Lumix 20/1.7 G. It was my mainstay lens on the E-PM1 Pen Mini, though I’ve used it less since acquiring the 12/2 and 45/1.8 lenses. Though it has a slightly longer real focal length at 40mm equivalent, in practice the difference is minimal and no more than a step or two backwards or forwards. The 20/1.7 is a popular lens amongst enthusiasts because it was both fast and compact; value for money, too, if purchased with the original GF1 kit. It still retains its popularity today, because the only other fast 35-ish equivalent so far has been the Voigtlander 17.5/0.95, which is not only hideously expensive, bulky and manual focus only – all of which somewhat defeat the point of Micro Four Thirds.

What I find curious is that the 20/1.7 images render as though they are a slightly cropped version of the 17/1.8 – this is a good thing, as the optics on the 20/1.7 are excellent. Sharpness/ resolution, microcontrast, color transmission and even quality of bokeh are very similar; however they have completely different optical design philosophies. Where the 17/1.8 makes significant gains over the 20/1.7 is in autofocus speed; it’s simply night and day; not to mention the usefulness of the manual focus clutch.

For the 35mm (or therabouts) EFOV enthusiast, we now have four choices in the Micro Four Thirds mount – the Olympus 17/1.8 and 2.8; the Panasonic 20/1.7, and the Voigtlander 17.5/0.95. There are also myriad other options you could adapt from other mounts, such as the excellent Zeiss ZM 18/4. I’d consider the adapted options not viable simply because none of them were designed with telecentricity in mind, yielding poor results on M4/3 cameras – severe vignetting, color shifts in the corners and purple fringing are all common problems. The Voigtlander is an intriguing lens and a surprisingly excellent performer at f1.4 (it’s decent at f0.95) that also happens to have a very short minimum focus distance of just 15mm from the sensor, but it’s very much a special-purpose lens: you don’t buy this and shoot it at f2.8. There’s simply no point. And if you need one, I think you’ll already know it.

That leaves us with the three native AF options. I would not buy the 17/2.8 unless size is a critical priority, or you know that you’re going to be shooting only static objects stopped down; otherwise the slow AF speed will drive you crazy. The Panasonic 20/1.7 is in a similar boat; it’s faster to focus than the 17/2.8 and optically better, but nowhere near as fast as the 17/1.8. The 20/1.7 and 17/1.8 deliver similar resolution in the center, but they render quite differently – the 20/1.7 is punchier but has slightly lower microcontrast; the 17/1.8 has lower macrocontrast but better reproduction of fine detail structures – i.e. better microcontrast. In the corners, the 20/1.7 is the highest-resolving of the three, but shows strong purple fringing on top of CA which is absent from the other lenses. Interestingly, one thing I noticed with all three lenses was that corner performance was not really consistent – i.e. there were some minor tolerance-related astigmatism effects in play. All three lenses still suffer from longitudinal CA and spherochromatism, though. Ultimately, I think your choice will boil down to three things: price (the lens is to be around US$500 when it becomes available in December), whether you prefer the 40mm FOV, or 35mm; and how critical is focusing speed? If you shoot a lot of street or documentary work, then the ability to stop down and scale focus can be an extremely valuable asset. Overall verdict: recommended. MT

Thank you to Olympus Malaysia for supplying the lens review sample.

The Olympus 17/1.8 is available here from B&H

____________

Visit our Teaching Store to up your photographic game – including Photoshop Workflow DVDs and customized Email School of Photography; or go mobile with the Photography Compendium for iPad. You can also get your gear from B&H and Amazon. Prices are the same as normal, however a small portion of your purchase value is referred back to me. Thanks!

Don’t forget to like us on Facebook and join the reader Flickr group!

Images and content copyright Ming Thein | mingthein.com 2012 onwards. All rights reserved

Experiments with street photography and motion

This series of images was captured around dusk in Shinjuku, Tokyo during my last workshop. While my students were off completing their final assignment, I decided to challenge myself to capture the feel and essence of the place in a different way to what I would have normally done. (After all, it wouldn’t be fair for me to put my students outside their comfort zone by insisting on the importance of having a central idea or theme in their images for their assignment if I couldn’t delivery myself, would it?)

At the same time, I’d felt as though I’d been reaching a little creative stagnation of late, and wanted to force myself to do something different anyway. Having your own style is good, but at the same time, that style has to evolve and grow in order not to get stale or boring. One of the things I’d been doing a lot of lately is jacking my shutter speeds up very high to ensure I was getting every last pixel of resolution out of the new cameras; whilst this made for great definition under the majority of circumstances, this crispness of capture doesn’t always suit the theme you’re trying to shoot to.

The idea I decided to follow for this series was flow – people as water, life as transient, a moment being more than a moment and altogether insufficient to capture the sheer volume of activity of what was going on around me. It’s a very strong impression I got simply by standing in place and watching life moving around me – people simply didn’t stop, torpedoing from location to location with some objective in mind, dispatching that objective, then moving on to the next one. (I’m guilty of this at times too; it’s a consequence of running your own business. Perhaps this experiment was as close to my subconscious was going to get to forcing me to slow down and smell the roses.)

The only two ways I could see of communicating this idea were either to have a huge number of people lining streets and thoroughfares to appear as a continuous mass (there were a lot of people, but not that many, and moreover there was no way or achieving that vantage point) or through the use of motion blur – not a little bit, of the kind that appears at 1/30s and with people walking, but something altogether a bit more abstract. In hindsight, this would have been very easy to accomplish with a tripod, but without it, I didn’t have the foresight to pack one in – much less bring one on the day. Even a mini-pod or a Gorillapod would have been useful.

Instead, I was forced to test the stabilizer of the OM-D to its limits – even with something to brace against (And sometimes not), I’d be needing shutter speeds in the 1/2s-1/5s range to achieve the effects I was looking for. Needless to say, you can only do this when the sun is going down. To give me a higher chance of success, I used the 12/2 for most of these shots, and shot in continuous high burst mode – not for the frame rate, but because I’d be able to keep my finger on the shutter button to minimize camera shake, and have only short intervals between frames. When I had to shoot using the LCD instead of the EVF, I would pull the neck strap tight to tension the camera somewhat against my neck and hopefully reduce shake – this technique is actually surprisingly effective. In hindsight, I should have used the self timer + burst function to completely eliminate finger-induced shake.

One of the things with this kind of photography is that you really don’t know exactly what you’re going to get until you get it; there may not be enough motion, or too much, or you might have streaks in the wrong part of the frame; all you can do is do a lot of takes until you get the right one.

Compositionally, the most important thing to remember when involving motion in your shot is that there must always be some clearly static and sharp object in the frame to serve as a visual anchor for your composition; if this is missing, the photograph just appears to be blurred or out of focus without the same directionality and focus that is implied by motion blur. In fact, having a large number of people moving through the frame is somewhat reminiscent of the energy of strong, dynamic brush strokes in a painting. I like the idea of abstracting out the people from the scene, and the contrast between the animate and inanimate. For these images, I chose the visual anchor first, then followed it by imagining where I’d want my flows of people to go; needless to say, there were a lot that didn’t work out because I didn’t have enough people moving close to the camera – a foreground is of course a necessity of using a wide-angle lens.

I did use the 45/1.8 for some of the images, but this proved to be extremely challenging as the lower practical limit for handholding a 90mm equivalent was somewhere in the 1/10s range on the OM-D, which is fractionally higher than what I needed for the desired effect. Still, I did manage to get lucky a couple of times with both very stable shots and convenient things to lean against. I also tried some more and less conventional techniques – panning blur, and combining staticness with abrupt motion of the entire camera to impose an impression of chaos whilst maintaining some semblance of a visual anchor. Overall, I’m pretty happy with the results though. Notes for a future experiment: I’d love to try this with a tripod and a longer lens. MT

____________

Visit our Teaching Store to up your photographic game – including Photoshop Workflow DVDs and customized Email School of Photography; or go mobile with the Photography Compendium for iPad. You can also get your gear from B&H and Amazon. Prices are the same as normal, however a small portion of your purchase value is referred back to me. Thanks!

Don’t forget to like us on Facebook and join the reader Flickr group!

Images and content copyright Ming Thein | mingthein.com 2012 onwards. All rights reserved

Photoessay: Street photography with the OM-D and ZD 60/2.8 macro

All images in this series shot with the Olympus OM-D and ZD 60/2.8 macro.

There’s nothing that says you can’t use macro lenses for non-macro purposes; the old myth of the optics being poorer at longer distances is just that: a myth. In fact, macro lenses tend to perform better than most standard lenses even at long distances because they are so well corrected in the first place. There are two drawbacks: firstly, the apertures tend to be slower, which isn’t so good for achieving subject separation and is solely a physical property of the focal length and aperture combination of the lens; secondly, the focus throw tends to be shorter.

Not wanting to be part of the crowd

This is a both good and bad – good because if an autofocus lens, the focusing elements don’t have to move as far since the lens must also be able to provide sufficient effective extension to focus at macro distances, bad because it means that if you have a manual focus lens – like the ZF.2 2/50 Makro-Planar I use – you have very, very little travel between mid distances – say 2-3m or so – and infinity, which can make precise focusing very difficult. For manual focus lenses, using the camera’s built-in rangefinder/ focus confirmation dot simply isn’t precise enough as the dot stays lit for some not inconsiderable displacement of the focusing barrel*. For autofocus lenses, the camera/ lens combination may not have the ability to consistently move the elements by the precise displacements required for very small changes in focusing distance – this is especially apparent with older screwdriver-focused lenses like the Nikon 60/2.8 D. Newer coreless motor lenses (AFS, EFS, M4/3 lenses etc) generally don’t have problems as there is very little backlash in the focusing system.

*Do this simple test to see what I mean: shoot the same subject, at the same distance, with the cameras on a tripod and your desired test lens attached. Using the viewdfinder or EVF, try to focus the lens/ camera manually from both infinity and near limit, stopping just once the focus confirm indicator lights. Do this with the aperture wide open, otherwise other focus errors like backfocusing or mirror misalignment can’t be identified and compensated for. Shoot the same frame again, focusing with live view to use as a comparison image. What you’ll probably see – is that neither image using focus confirm is as sharp as the live view image. This effect is even worse for telephotos, because of the depth of field characteristics of the focal length. The shorter the focus throw, the worse this problem becomes.

Potential focusing issues notwithstanding, so long as you have enough light for a sufficiently high shutter speed to avoid camera shake, the results are generally excellent. Specifically in the case of the ZD60, (my full review at macro distances is here) I’m pleased to report that the lens’ already excellent optical properties do not change at all at longer distances. In fact, the one niggling flaw I saw at close range is mostly gone – I’m not seeing any bright edges to out of focus highlights. Both foreground and background bokeh is smooth and non-distracting. Subjects fall nicely in planes and are separated in a manner that has plenty of 3D pop; this is characteristic of a lens with excellent microcontrast.

Focusing is not an issue at all, and is just as fast as the ZD 45/1.8 providing you have the 4-way limiter switch in the right position. The one minor issue I did find was that the lens with hood is not exactly inconspicuous (and nowhere as compact as the 45), being nearly 15cm long with everything in place. Relatively small by DSLR standards, but probably not exactly what M4/3 users have in mind.. Personally, I find this combination of interest not because I’d take it out on dedicated street photography/ travel expeditions, but because I frequently carry the OM-D system either as a backup camera (or as a primary for assignments that don’t require the D800E’s resolution) – and the ability for a lens to do double-duty means one less thing to carry, break, fail or potentially lose. It’s always nice to have options. MT

The Olympus OM-D, 60/2.8 Macro and 45/1.8 are available through Amazon by clicking on their respective links.

____________

Visit our Teaching Store to up your photographic game – including Photoshop Workflow DVDs and customized Email School of Photography; or go mobile with the Photography Compendium for iPad. You can also get your gear from B&H and Amazon. Prices are the same as normal, however a small portion of your purchase value is referred back to me. Thanks!

Don’t forget to like us on Facebook and join the reader Flickr group!

Images and content copyright Ming Thein | mingthein.com 2012 onwards. All rights reserved

Quick review: The Olympus 15/8 Body Cap Lens

At left: body cap. At right: Lens. Not much difference.

Disclaimer: if you came here looking for optical perfection, you should probably stop reading now.

On the other hand, if you came here because you were curious about this little pancake, then read on. I admit that although I’m usually squarely in the former category, for some odd reason, the 15/8 got me intrigued – I suppose it was the size, or the fact that it suits the whole ‘fun’ ethos of the smaller PEN cameras. I think it’s the photojournalist in me that very much likes the idea of having the camera ready to go at all times, even if it’s in storage; the Olympus BCL-15 lets you do just that. It’s effectively the same depth as the supplied standard body cap (maybe a millimetre or two thicker, but nobody’s counting) – making the smaller bodies like the E-PL5 and E-PM1 very pocketable indeed. The lens was launched together with a number of other items at Photokina 2012 – notably the E-PL5, E-PM1 Pens, 60/2.8 Macro and the wireless SD card system.

The mosque by the sea. E-PL5, 15/8

It isn’t anything special in terms of construction: the lens has just three elements (supposedly glass), all-plastic construction, and a clever little lever that both doubles as a shutter to protect the front element, as well as a focusing lever; on the subject of focusing, you can get as close as 30cm to your subject. The lever is light and doesn’t really stay in place if bumped, but then again, precision isn’t that important in a lens that both has an extremely great depth of field – being a 15mm f8 and all – and optics that aren’t exactly highly-corrected. In fact, it’s a wonder that it isn’t just fix-focused.

Needless to say, there’s no electronic communication of any sort between camera and lens, so EXIF data is not recorded, and since there’s only one aperture, you’ve effectively got a point and shoot. Curiously though, it appears Olympus has put a small baffle between two of the elements to only use the central portion of the lens in a bid to keep image quality reasonably high; I suspect that if one could somehow separate the elements and remove this, you’d find the lens to be closer to f4 or thereabouts – at the expense of optical quality and depth of field, of course. It might be something I’d be willing to try as a rainy day project…

So how does it perform optically? Well, it’s surprisingly sharp in the center, even though the 16MP M4/3 sensors are already hitting diffraction limits at f5.6 and smaller; the lens might well be a bit sharper if it was a stop faster due to this. The edges and corners are another story – let’s just say they’re not very sharp anywhere, and rather smeary in places. No doubt this is due to the limited optical correction possible with just three non-aspherical elements. (That said, this lens reminds me of the MS-Optical Perar Triplet 35/3.5 and 28/4 lenses for the Leica M mount; I wonder how they perform optically.) So long as you keep your subjects in the central third or so of the the frame, and take a little time to ensure focus is just about at the right distance, optical results are better than expected.

Although you might think that some of the crops are soft because of the focus distance, let me assure you that at f8 and a 15mm real focal length, the depth of field is more than sufficient to cover where I placed the focal point – and that was verified with live view magnificaiton for the purposes of this test; in real life, I don’t think I’d bother.

Simple lens designs like this one tend to have very high contrast and transmission because there aren’t a lot of surfaces and air-glass interfaces inside the lens to lose light at; the 15/8 renders with very high macrocontrast indeed; microcontrast is much less impressive, though (and has a lot to do with resolving power – you weren’t surprised about that result, were you?). Color is saturated, brilliant and actually quite pleasing.

I can see photographers buying this for several reasons – as a fun walk around lens; as an impulse buy when you go to the camera shop with itchy fingers but perhaps not enough money or not finding anything that really catches your eye; the blogging crowd will probably find it fun and conveniently compact. I actually used it a lot while reviewing the E-PL5 (which all of these images were shot on) simply because it made the camera very pocketable and immediately responsive – not having AF and all – and being very close to my preferred 28mm focal length, an interesting street photography option (at least in good light; f8 means that you’re hitting ISO 3200 even in the shade, and forget about using it indoors).

Amusement park dusk. E-PL5, 15/8

Conclusion: At just US$60, it’s a no-brainer recommendation for anybody who owns a M4/3 camera, especially if you’ve got a older or spare one lying around. Mine now lives on my E-PM1 Pen Mini, which has seen little use since the OM-D and Sony RX100 entered the stable. put this on, stick the camera in your pocket, and go for a walk. You’ll be glad you did. MT

The Olympus BCL-15mm f8 Body Cap lens is available here from B&H or Amazon.

____________

Visit our Teaching Store to up your photographic game – including Photoshop Workflow DVDs and customized Email School of Photography; or go mobile with the Photography Compendium for iPad. You can also get your gear from B&H and Amazon. Prices are the same as normal, however a small portion of your purchase value is referred back to me. Thanks!

Don’t forget to like us on Facebook and join the reader Flickr group!

Images and content copyright Ming Thein | mingthein.com 2012 onwards. All rights reserved