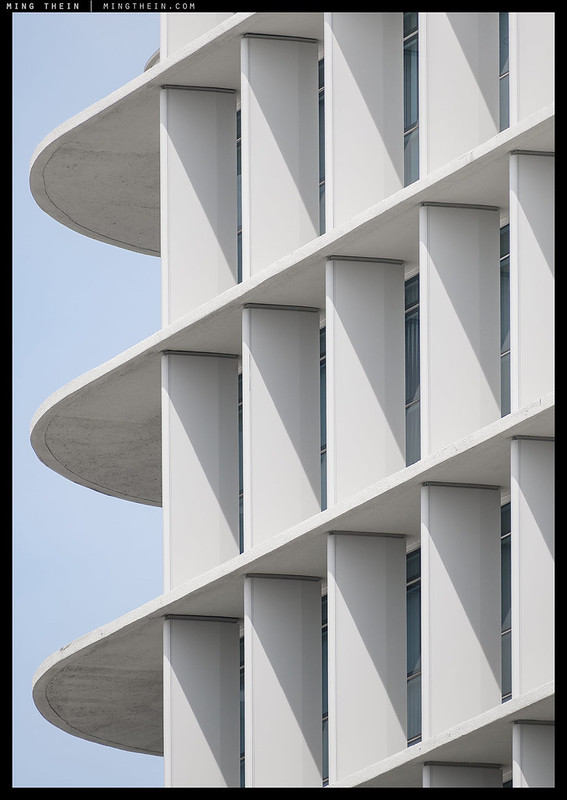

Glitches in the Matrix

Limitations can sometimes turn into catalysts if they force you to find creative workarounds, or give you another tool in the arsenal to work with. This tale is one of regret – that I recognized the limitation, but came to be so annoyed by it I sold the tool instead of being mature enough to recognize the opportunity.

Almost all large sensors – including most of those today, and certainly all of the high resolution ones – have a gated electronic shutter that requires a certain readout time. Light collection is limited and governed by the mechanical shutter, ensuring synchronization of exposure of all parts of the image – but the actual capture time may go on beyond the closing of the shutter. It’s fast enough now that high frame rates may be sustained, but you can still see these artefacts in electronic shutter modes as a distortion from top to bottom of the frame of any moving elements (or moving camera).

The CFV-39 was a bit different: not only did the CCD have an extremely long readout time – I believe at least a second – but the camera portion and the digital portion were only synchronized by a button; the same pin that advanced the frame counter on a film back also started and stopped the digital back capture (and actual sensor on time was much longer than the shutter-governed exposure).

The upshot of this is if your fingers were fast enough to cock the crank and hit the shutter, you could fire off two frames in less time than the CCD required to read out completely. In effect, this disrupted the readout process with a fresh signal onto the sensor – it appeared something like a double exposure but with some other strange and unpredictable artefacts. I learned to count to three before firing the back again to avoid this, but there were times of peak action where one or two very strange frames such as this one were produced. Between the color, the subject matter, and the alien feel – I couldn’t help but think of the déjà vu scene in that 1999 cult classic movie…