Hanoi is one of the more interesting places I’ve been recently – these images were shot during downtime on a business trip about a year ago. It’s a fascinating mix of French colonial and Southeast Asian chaos; juxtapositions abound, and rich textures are plenty – making for great shooting. Part one, in color. I’m told Ho Chi Minh City is a lot more developed an interesting, but I haven’t had a chance to visit yet. MT

This set shot with a Nikon D700, 85/1.4G and 28-300/3.5-5.6 VR.

Quantum mechanics at work again: the scene changed because the subjects noticed the photographer.

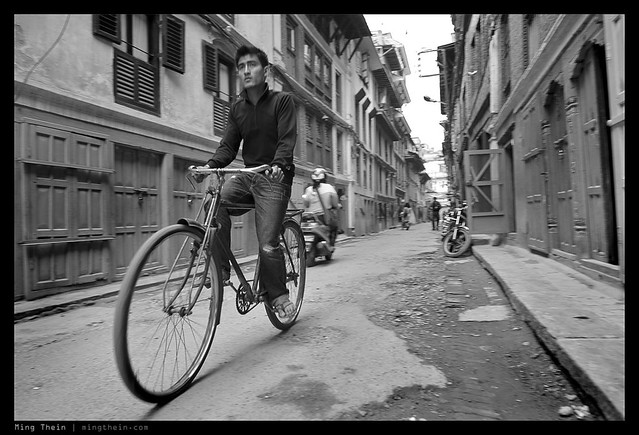

A vomit-inducing ride. Notice passenger on the right hand bike.