A recent email from a beginner/ amateur user on which camera settings to use under what conditions provided the motivation for this post. In addition to there never being a one-size-fits-all answer, it occurred to me that the reason why a lot of users are confused is partially down to poor product and UI design on the part of the camera companies, and overambition on the part of the user.

Cameras tend to come in one of two flavors: firstly, fully automated, dumbing down, hiding or completely eliminating all photographic functions/ controls or obfuscating them to the user behind language or parameters that doesn’t necessarily make sense intuitively, such as ‘blur control’. The second type of camera lets it all hang out: it’s so manually intimidating and complex, offering control over everything from critical exposure functions to the color of the LCD backlight or number of images taken when using the self timer, and at what interval – that the new or even slightly unfamiliar user has no idea where to begin. And to compound things, camera makers often make inexplicably baffling changes to the UI between each generation – for instance, the +/- indicators on the exposure compensation scale for the D700/D3 generation runs in the opposite direction to the D800/D4. Why? Nobody knows. Maybe the person designing the silk screen stencil for the top panel LCD didn’t refer to the previous model, or think that there might be photographers out there still using both generations of camera. (Sure, you can make the rotation direction of the dials match, but it doesn’t help the fact that either way, one of the cameras is going to have the display move in an unintuitive direction in use – which may slow you down enough to miss a shot, or you ignore it and land up drastically over- or under- exposed.)

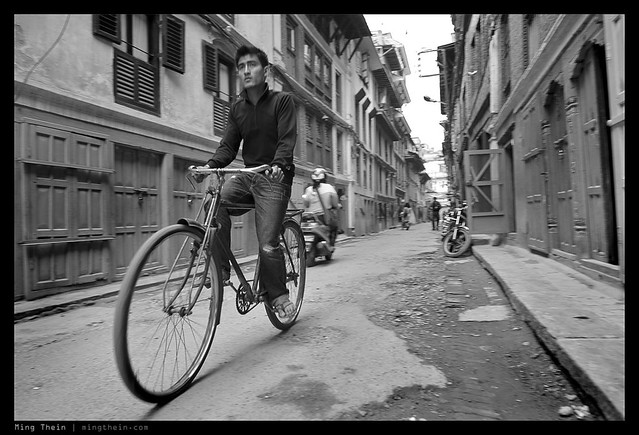

Human nature forms the other barrier: whilst most of us have a decent idea of the limits of their own ability, we might not be so willing to admit it to others. And like it or not, in today’s consumer society, the size and complexity of your camera is a subtle, or perhaps not-so-subtle, telegraph to the rest of the world about both your spending power and your photographic prowess. (Of course, whether either is accurate or not is a completely different topic.) It seems to be especially true where I live, where you see almost everybody carrying a DSLR – yet using it in the green mode and looking surprised when the flash pops up by itself. The upshot of this is that almost every consumer will buy more camera than they need, either convinced by the marketing mantra of ‘more better’, the smooth-talking salesperson, wanting to outdo their friends, or thinking they can ‘grow into it’.

A casual survey of my non-serious-photographer friends reveals that most of them don’t know how to do anything more than turn the camera on, zoom, press the shutter to take a picture; and perhaps turn the flash on and off. It also makes me wonder why ‘simple’ compacts are still so darn complicated to operate. The disconnect is that there are also a good number of them using prosumer DSLRs – think D7000s or 60Ds and the like. It’s both a shame for them that due to the intimidating nature of the cameras, they may never progress any further; yet be frustrated that the camera doesn’t behave quite as expected. Why is the shot dark? Why is it always focusing on the background? Etc.

Important photographic controls boil down to two things: one set that controls the look of the image, and one set that controls the behaviour of the camera.

Image parameters, in order of importance

Focal length – The perspective and field of view of your frame. Note that this comes before all other considerations, because if you misuse your perspective or select the wrong field of view for a given subject, then no matter how technically perfect the image, it won’t save you from poor composition.

Aperture – The size of the lens opening; controls both the amount of light entering the camera, as well as the depth of field or the range that is in focus. Smaller f-numbers indicate a larger opening, which equals more light and higher shutter speeds, but also shallower depth of field. Isolate subjects with out-of-focus backgrounds by using a larger aperture. Using a small aperture in low light will yield insufficient shutter speed to produce a sharp image unless you’re using a tripod or very high ISO.

Shutter speed – The amount of time for which the shutter stays open. The longer this duration, the higher the chance of you, or the subject moving, and subsequently producing a blurred image. This can be desirable if there are clearly static elements in the scene to serve as a visual anchor point, such as rocks and blurred water, etc. The faster the subject, the higher the shutter speed you need to freeze its motion. To handhold a reasonably high-resolution camera safely and produce an image that is crisp at the 100% actual-pixel level (assuming the subject is in focus), you need 1/[focal length in 35mm equivalent]s, or half that (1/2x) to be safe.

Sensitivity/ ISO – The ‘gain’ or amplification on the signal from the sensor. Doubling the ISO doubles the gain, which in turn doubles the shutter speed. However, you’re also doubling both the information part of the signal as well as the noise, so every increase in ISO necessarily comes with an associated penalty in image noise. However, most cameras have a decent usable range that makes it possible to set auto-ISO within this range, and let the camera automatically boost sensitivity when the shutter speed falls below the set threshold (usually 1/focal length or faster) – this way you both never miss a shot due to insufficient shutter speed, and cameras can frequently set finer increments than is possible manually, minimizing noise.

White balance – The neutral color point of the image, or the RGB gain mix required to achieve white under a particular ambient lighting situation. For the most part, you can leave this in automatic and tweak the RAW file afterwards; however for extremely warm or cold ambient light (tungsten, shade) you may want to manually choose the respective presets to prevent overexposure of a single channel – once a channel is blown, you can’t recover it afterwards.

Note that the simple way to reduce your workload is to run the camera in aperture priority, auto-ISO and auto-white balance; just make sure that your selected shutter speed thresholds for auto-ISO fall within your desired range – slower if you want to blur motion or are using a wider lens, and vice versa. I normally have my cameras configured this way, unless I’m doing work that requires me to balance flash and ambient, or color-critical work; in which case I’ll go manual for everything.

Camera control parameters, in order of importance

Focus point/area – The shallower the depth of field, the more important it is to have some control over exactly what the camera is focusing on. Without this, you will find your subject out of focus – especially if off center. The camera can’t read your mind (or at least not yet). This said, put your camera in either center point and do the focus-half press to lock-then recompose technique, or choose your focus point manually. Make sure your subject is the most contrasty thing under the selected point, and large enough to be picked up by the AF system.

Focus mode – Single (AF-S), continuous (AF-C), or manual (MF)? Single means that the camera stops focusing once focus has been achieved for the first time. This is good for static subjects. Continuous means that the camera will continue to adjust focus until you release the shutter, which is desirable for moving subjects or very shallow depth of field lenses (a situation that may appear static – a portrait, say – may actually have motion of a few millimetres in either direction by the subject or photographer, and that’s enough to cause noticeable softness when using a very shallow depth of field lens). And finally, manual focus of course means DIY. I always have my phase detect AF cameras (DSLRs) set in AF-C, and the contrast detect cameras in AF-S; the reason for the latter choice is simple: the hit rate is much higher, and contrast detect cameras all have smaller sensors, which makes them more tolerant of minor focus errors.

And to be honest, the rest you really don’t need to worry about. For years, we’ve managed with nothing but these controls – in fact, in the early film days, you couldn’t even change your ISO easily from shot to shot, there was no such thing as colour, and there was no such thing as AF-Tracking – so really, you should be able to make a strong image focusing only on three of the parameters.

Master these, and you’ll find that you now feel in control of your camera and the images it produces, instead of vice-versa. Shooting fully manual is a good way to both learn to control your camera instinctively, as well as build an intuitive understanding for how changing a given parameter affects the look of the image; eventually you’ll build a sense for what the right parameters should be for a given shooting situation. Even if you’re an experienced photographer, sometimes a little reminder to reprioritize the important things can be helpful – the fewer things you have to think about when shooting, the better. Note that we haven’t touched on composition – that was the subject of extensive analysis in this article. MT

____________

Visit our Teaching Store to up your photographic game – including Photoshop Workflow DVDs and customized Email School of Photography; or go mobile with the Photography Compendium for iPad. You can also get your gear from B&H and Amazon. Prices are the same as normal, however a small portion of your purchase value is referred back to me. Thanks!

Don’t forget to like us on Facebook and join the reader Flickr group!

Images and content copyright Ming Thein | mingthein.com 2012 onwards. All rights reserved