Goldeneye steamed in miso and ginger

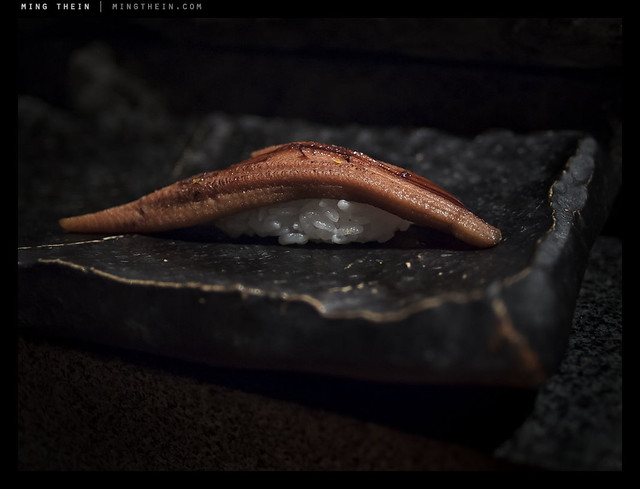

Seared tai (seabream) with momeji oroshii chili.

Iso-bagai snail, I believe poached in mirin and soy.

This series shot with a Nikon D800, PC-E 85/2.8 D Micro, and two LED light panels. Chef – Kenny Yew at Hanare

Two of the toughest things to get right color-wise (in my experience, at any rate) are people and food. There’s something about the way organic materials reflect light – probably due to the fact that they are both reflective, transmissive, and have odd properties in the infrared and ultraviolet regions (think: flowers, or cat’s eyes) which is just a huge challenge for most cameras.

Up to this point, I was fairly convinced that the Olympus Pen Mini plus Zeiss lenses (usually ZF.2 2/28 via adaptor) delivered hands down the best color; perhaps not the most accurate, but certainly the most pleasing. The Olympus sensor’s color bias would take care of global saturation and hue, and the Zeiss glass would ensure great micro contrast and accurate color transmission. Similarly, for landscapes – anything with skies, especially – the Leica M8/M9s excelled; I still can’t match the blue with any other camera. To my eyes, the Leicas (with Leica lenses) deliver the best sky blue bar none; and a decent skin tone (with Zeiss lenses – yes, there is a difference in color transmission; it’s subtle but I’ve always felt the Zeisses are slightly warmer.) The Nikons…well, I learned to correct them, but frankly, they weren’t that accurate (thought the D700/D3/D3s was the best of the bunch to date). I think it has something to do with the way Nikon designs lenses for global contrast rather than micro contrast, which affects the transmission of subtle tonal variations. Color improves markedly with Zeiss glass, which is designed to optimize micro contrast.

After this shoot, however, I think I’ve stumbled upon the best of both worlds. The D800’s sensor delivers the best color I’ve ever seen – accurate and highly pleasing, which is an achievement (and I believe DXOMark found the same thing). Paired with the Zeiss 2/28 Distagon, it’s pretty incredible. But what if it could get better? What if you could have accuracy, saturation, micro contrast, macro contrast and everything in between? Apparently, you can. The PC-E Micro-Nikkors now take the cake for me as the best lenses to use with the D800; resolving power is there even wide open; color transmission and micro contrast are on par with the Zeisses; edge performance isn’t an issue because they were designed with enormous image circles to support the tilt shift movements; and finally, you solve the DOF vs diffraction issue through tilts or swings.

My only complaint is that focusing ring feel is rather inconsistent, for some inexplicable reason. The 24 PCE is silky smooth; the 85 PCE is so stiff and dry that it’s very difficult to move in small increments. And sadly, Nikon has changed some components internally so that moving the tilt and shift axes to be parallel now requires new internal PCBs and about $400, instead of just removing some screws. This begs the obvious question: why the hell didn’t they design it that way in the first place, since a) clearly, enough people want the lens that way that they designed a separate PCB for such cases; b) almost all of the lenses I’ve seen on ebay have been modified and c) it doesn’t make any sense photographically unless you want to do a horizontal pano! For architectural work, macro work, and everything else, you need to have tilt and rise/ fall, not tilt and shift or swing and rise/ fall. Makes you wonder if anybody is actually a photographer on the lens design team.

All of that aside, being able to shoot at wide open or nearly wide open and still have sufficient DoF is a joy. It makes small LED light panels useable as your primary light source at ISO 100, handheld even. This is great, because studio strobes and speedlights will make the food wilt in double time, and anything raw will start to look slightly parboiled under the heat if you don’t work fast. On that note, enjoy the sushi. MT