MF tonality and separation: in the full size image, the airplane is in a clearly different focal plane to the tree and hangar – even though it was shot at f8.

I’ve written previously about what exactly contributes to the ‘medium format look’. However, I think to some degree we also need to both define what constitutes the hallmarks of smaller formats, but more importantly figure out where each format’s strengths lie. Having now shot what I’d consider ‘enough’ with a complete MF system wth lenses ranging from ultra wide (24mm, or 18mm-e) to moderate tele (250mm, or 180mm-e) I think I’ve built up a much more complete picture. No doubt this will change if the recording medium size increase further – with the 54x40mm sensors, for instance – but I think it’s fairly safe to extrapolate based on the differences between subsequent smaller formats.

Compositions like this do not work without extended DOF, but the perspective limits your format size in achieving that.

Depth of field

This is probably the most immediate giveaway: for a given subject magnification, aperture and angle of view, larger formats will appear to have shallower depth of field. Remember that the real focal length and aperture are what determines the degree of background blur; the larger the format, the longer the lens required to cover that angle of view. Even though lenses tend to get slower as the format increases – faster apertures for longer real focal lengths are harder to build – in practice, what we notice is larger formats have some degree of separation between subject and background/foreground planes, where smaller formats may not. However, this may require larger output sizes or resolutions to discern; 1MP web jpegs are almost certainly going to be missing something. It gets a bit more complicated, though: for an ideal lens, the transition between in and out of focus becomes significantly more abrupt as the focal length increases. With a shorter real focal length, that transition might be very gradual – and thus appear to have almost no visual separation at all.

Angles of view, projection and optical formulae

That said, things get more complicated still: longer lenses are easier to fully correct for, which means optical formula limitations that degrade our perception of sharpness of transition (think of an image ‘sliced into planes’ ) such as coma, longitudinal and lateral chromatic aberration are more easily minimised. When these aberrations don’t ‘eat into’ the edges of the focal plane, we are given the impression of shallower depth of field because the boundary of confusion is much tighter – a subject is either in focus, or it is not.

24mm, and 16mm-e, but no strange edge stretching.

On the reverse side, when engineering for shorter real focal lengths, all sorts of other problems must be taken into account. For instance, if the design requires a relatively long image distance compared to the actual focal length (e.g. Nikon F back flange, ~47mm, focal length, 21mm) then a telecentric design must be used, which contains another set of elements to ‘straighten out’ and extend the ray path so that it might focus the projected image at the correct distance. Even if not, and we are using a system with a short flange back distance – symmetric designs aren’t always ideal because you’re going to land up with very extreme ray angles towards the edges. Since digital sensors are not truly planar but more like a waffle grid, interactions at the edges of the individual photosite can produce both vignetting and purple fringing towards the edges of the sensor. Offset microlenses over the photosites can compensate for this to some degree, but the potential for aberrations to start affecting transitions remains high. This is one of the reasons a lot of fast wide lenses lack the sort of clean transition you’d otherwise expect.

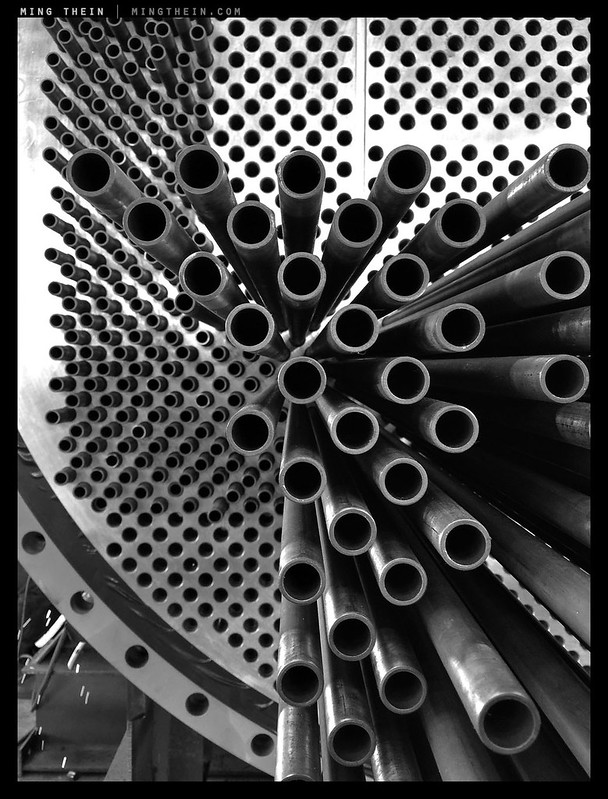

Impossible DOF and perspective for anything but a very, very small sensor. Foreground pipes are barely 20cm from the lens.

But, we’re still not done yet. Even though the perspective (foreground-background) relationships between objects remain the same for a given angle of view, there are practical optical design issues to contend with. In general, the shorter the real focal length and the larger the format, the more projection distortion becomes visible without resorting to very exotic optics: think of squashing a printed balloon onto a glass window, or translating a globe to a flat map. We can represent a map of the world on a 2D surface, but it requires some cutting and/or stretching (which is how we land up with things like the Mercator, Hammer, Panini etc. projections). Stretching is necessary should we want to present a continuous surface, which obviously causes some distortion to the image being projected – we see this as corner smearing or stretching. All lenses have some degree of field (focal plane) curvature, which becomes harder and harder to correct for as the focal length becomes shorter and the angle of view wider.

The wider you get, the worse this becomes. Once you pair that with the inherent difficulties of shorter real focal lengths and physically smaller lenses (i.e. fewer elements, less image circle to work with) – you can probably see why it’s easier to design a 50mm lens with a 60mm back flange distance (~1:1.2, 645 format) than a 30mm one with a 47mm back flange (~1:1.6, 35mm-e), even though they cover the same angle of view. As this ratio gets larger, design becomes exponentially more difficult for reasons previously described. Every time you want to correct for something – telecentricity, field curvature, distortion etc. – you introduce additional elements which must themselves in turn be corrected for.

Heavily corrected, but distortion is still visible.

Sensor proprettes

In the earlier article, I also touched upon some of the underlying media differences: no longer do we have the same recording medium in different areas, but physically larger sensors will a) not just have greater spatial resolving power for the same output resolution, but b) generally have larger photo sites and greater spatial resolving power. This leads to significant gaps in dynamic range, noise and in turn, color resolution. On top of that, the potential for greater spatial differentiation leads to much better tonal separation and subtlety: you’ve got a lot more steps to describe the same transition.

These differences must be considered together, mostly because of simple economics: smaller/worse/cheaper vs bigger/better/more expensive. There aren’t any really bad MF lenses because the underlying cost of the main component (sensor) determines the pricing level anyway; however, there aren’t that many good entry level kit lenses for similar reasons. In practice, I believe what this means is that there’s a sweet spot for every format/system; however, this isn’t immediately obvious to most people as few have shot a variety of systems under an equally wide range of conditions. My personal feeling is that there really isn’t a one-size-fits all both because of underlying system characteristics (e.g. small vs large sensors and attendant body features such as AF) and because no one system can give you a sufficiently wide variety of rendering styles. By sensor size, here’s where I think the strengths and weakness lie:

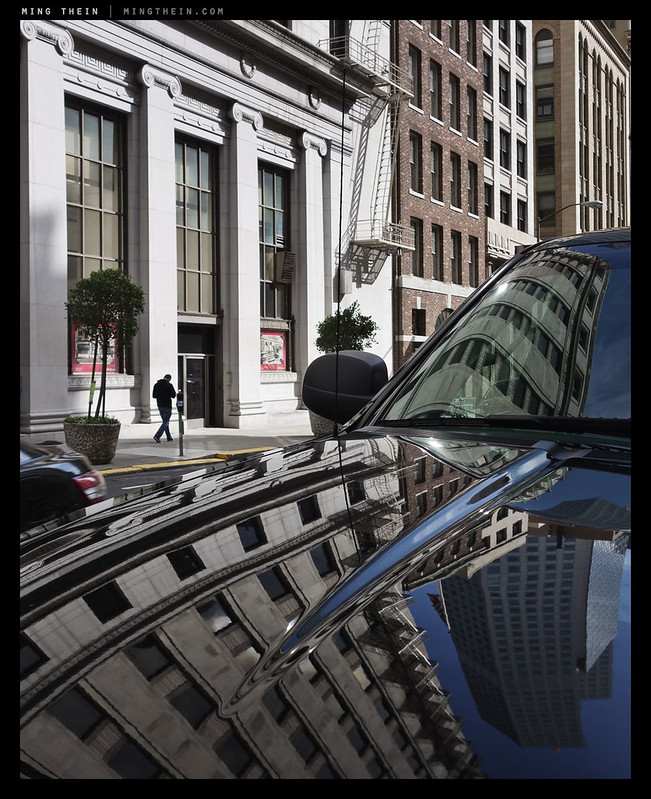

Those impossible compressions…

Compact, phone

Good for: Casual documentary, stealthy documentary, social record. Small size and ubiquity means you are inconspicuous; small sensor means you have almost unlimited depth of field and minimal focusing issues. Fast to use because there are few parameters to control (e.g. changing aperture makes no difference anyway, focus distance only when below a certain range).

Limitations: No DOF separation, restricted dynamic range and poor overall image quality, few options other than a wide FOV.

1″

Good for: I’m struggling a bit here. They’re a bit better than the compacts, but not so much that you’d be happy with one of these for primary output. Rendering of wide options tends to be quite uninspiring and just a bit messy looking: there’s enough depth of field differentiation to make transitions nervous, but not so much DOF that everything is in focus. The biggest strength I can see is for highly compressed telephoto perspectives where everything is in focus – the crop factor means you have much greater DOF than you might think for a given aperture, plus light gathering ability doesn’t become so much of a problem.

Not good for: Similar limitations to compacts and phones, but more lenses available.

M4/3″ and APSC

Good for: Given the lens selections, this isn’t a bad all-round solution for most people. I still haven’t found any wides whose rendering I really like, though – for the all the reasons we previously discussed. I think the main strength is again telephoto work: excellent small lenses with fast apertures (thanks to crop factor) offering enough separation (and not so little you have problems getting enough of the subject in focus) but still the option to get everything in focus if you need to.

Not good for: Wide angle work; a consequence of lens design and simple physics: the wider the field of view, the more spatial information (i.e. resolution) you need to avoid a gritty look.

But sometimes, you might want that gritty look…

35 FF

Good for: General shallow DOF work, moderate wide to moderate tele, supertele with shallow DOF. I think most people have realised by now that to get a wide range of distances in focus with high resolution 35FF bodies, you’ll either need to stop down past the diffraction limit, be shooting pretty wide and/or with subjects constrained beyond a certain distance, or use perspective control (i.e. tilt). Yet because of the completeness of the attendant systems, 35FF remains the all-round choice format: everything from 8-800+mm in a single lens without TCs, plus perspective control and macro.

Not good for: Getting everything in focus outside wides or what tilt shifts are on offer; subtle separation at wide/normal angles of view

50mm, f8, and it’s clearly not even close to all being in focus. Yet the appearance of transition itself is quite natural…

MF digital (44×33, 645-54×40)

Good for: Superwide to moderate telephoto; getting some sort of DOF separation at all distances and focal lengths even with moderate lens speeds

Not good for: Getting everything in focus without the use of tilt shift adaptors or putting the back on a technical camera, telephoto work, anything fast moving

LF

Good for: Full perspective and DOF control, a very ‘flat’ look no matter what the angle of view – minimal distortion and clean projections

Not good for: Anything where you don’t have space for a tripod and several minutes to set up each shot, digital work with the full format area

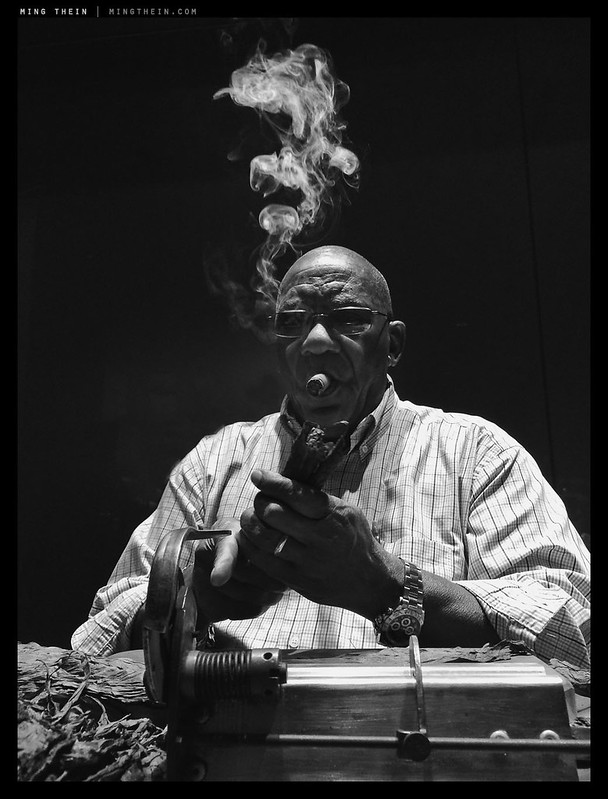

This kind of tonal subtlety remains the main reason to go larger.

There are three ways of approaching this: either select the format that will give you the greatest coverage of the kinds of things you normally shoot; restrict yourself to one format that produces results of the kind you want to produce; or, have multiple systems (or a system that allows for some interchangeability of lenses and sensor sizes, e.g. Nikon 1/CX, Nikon APSC and Nikon FX: three bodies, one set of lenses). I’ve gone down the multiple system route because I found the the adaptations simply don’t work that well – it usually isn’t a limitation of optics, but the whole thing just becomes very clunky in use. But of course, we also must remember that doing something differently with unconventional formats almost always yields unusual (and sometimes quite aesthetically pleasing) results…MT

__________________

Ultraprints from this series are available on request here

__________________

Visit the Teaching Store to up your photographic game – including workshop and Photoshop Workflow videos and the customized Email School of Photography. You can also support the site by purchasing from B&H and Amazon – thanks!

We are also on Facebook and there is a curated reader Flickr pool.

Images and content copyright Ming Thein | mingthein.com 2012 onwards. All rights reserved

My local retailer has a used E-M5 (first gen) for $285 and I’m tempted to take the plunge just to have a small and light everyday/travel-camera (paired with the 25/1.8 and 45/1.8) Is it still worth it after all these years or should I save my money for something else?

Can’t honestly say not having used one for many years now. But at $285 I’d add a little more and get the D3500.

I’ve always followed that “Namely that we should avoid shooting wider than f5.6 if we want optimal sharpness” rule without much thinking. After all, lens reviews seem to always conclude sharpness peaks about here. Then a few months ago I heard or read Salgado say he always prefers to shoot stopped down to f/16 or more for optimal depth of field, saying something like “Why wouldn’t you want everything to be in focus?” His Genesis project consists primarily of landscape/wildlife/nature photographs, of course, but as soon as someone like him says something so obvious you realize that following a simplistic recommendation for “optimal sharpness” without adding “for what purpose?” is rather embarrassing. I’ve never heard anyone criticize his photographs for not being sharp enough! Repetition and consensus can really limit your own thinking. Ming’s blog is especially useful for making us all rethink things.

Salgado’s compositions support all-in-focus background elements as part of the structure of the image and in turn the context/story to the subject; they might work with some DOF isolation but too much and you’d lose the story entirely. The story is in turn powerful enough to outweigh the technical flaws of the image, which believe me, are there – just look at the lack of consistency in presentation/processing in the Genesis series. Would it be better with higher technical qualities? Yes. Does the overall idea suffer for the lack of them? Not so much.

Very intriguing, thanks for the article. Does the short flange distance of mirrorless cameras alter the recommendations for any given sensor size?

No, it just alters the optical design requirements of the lenses.

With smaller mirrorless camera bodies the thought of carrying two different format cameras with the ideal lenses attached is becoming more and more attractive. For me it used to be Nikon DX and FX… now it could even be FX and MFT. Need to work out the weight…

FX and M4/3 is interesting because you can do fast and/or wide on the former and have very decent telephoto reach on the latter, but without much difference in size. However – I’ve also found that DX-cropping a 47MP FX file (resulting in 20MP or so_ to be comparable to ‘native’ APSC…

A brilliant article. I use the Hasselblad X1d for wide to moderate telephoto and M4/3 G9 system with normal to long telephoto primes. The Pana Leica 200mm is an incredible lens with amazing sharpness and rendering. It even comes with a 1.4x converter that if you stop down one stop I see no difference – and I can carry it and handhold it.

Thanks. Pricing for some of the new Panasonic lenses is downright scary though!

Hello Ming. I love reading your articles. I currently own (Micro 4/3, FF) Digital, and Film MF 6×7. Money aside what do you estimate to be the ideal focal length for these formats? I am always looking for that separation at times and only seem to achieve with MF 6×7 and now I can understand why, thank you. Base on your explanation I am thinking ideal primes per format would be 45-90mm for 6×7 MF, 50-100mm for FF, and 150->mm for Micro 4/3. Am I on the right track with this thinking. I don’t mind different systems. I actually enjoy it. This is my hobby I do not shot for pay. Also did you see a difference in the MF look between your images from 6×6 MF film vs Digital MF since it is a smaller format. Thanks God Bless you and your family.

6×6 vs smaller MF – there IS a difference in perceived separation, but the smaller format lenses were newer and better, so I feel there’s also an increase in acuity/ clarity – it’s not as obvious as with smaller formats but is still there. More obvious of course between say 6×6 and 33×44 (than 54×40).

Since I shoot both Four Thirds and full frame, last year I started an experiment that is ongoing. I started shooting with the aperture wider. Typically f3.5 or f4. I reasoned that an image that worked well when shot at f8, with my Sony kit, should work well if shot with the equivalent focal length at f4, on Four Thirds. This brings us into collision with one of the orthodoxies of photography (as laid down by countless members of countless forums). Namely that we should avoid shooting wider than f5.6 if we want optimal sharpness. From my results so far, I reckon with modern lens design this orthodoxy is perhaps not as relevant as it once was. Especially if we’re using a lens system built from the ground up, and optimized for, the format (e.g. Four Thirds or Fuji/Leica APS-C).

That said, even when shooting with equivalent aperture and focal length, there are subtle differences between full frame and the smaller format. If we consider the overall width of the shooting envelope (including factoring in the kit actually being with you), I suspect mirrorless full frame edges it.

Not true – increasingly, modern lenses are optimised for performance wide open or very close to it. For recent top-flight designs, I see an increase in depth of field with stopping down (and thus with some subjects, perceptual increases in sharpness) – but no actual increase in resolution at the imaging plane.

Agreed, FF mirrorless with fast lenses, IBIS and accurate focus on the sensor plane has the widest shooting envelope of any camera system right now – something like a Z6 with f1.4 primes can make a better image in low light than even our eyes.

Thank you for this article. It’s taken awhile, but I’ve gone the multiple camera route as well. Nikon D7500 with 16-80mm and Nikon D750 with 28mm 1.8 and 58mm 1.4. For reasons similar to what you described. I like the zoom on Nikon DX, smaller, more compact, and more DOF. Fun to use. And the primes on Nikon FX for more DOF, greater range of aperture. I also have a 70-300mm that I can use on both cameras. I’m kind of a mind that DX is a zoom system and FX a prime system, but only in regards to what I like to do of course. (And the D750 and D7500 are similar enough that it’s easy to switch between them).

Actually, you’re playing to the strengths of both systems: slower zooms for more DOF and greater angle of view range on the smaller sensor; shallower DOF and better low light capabilities on the larger sensor. Doing it the other way around would result in more similar images, not different.

Thanks for this post. Maybe it’s not crazy to have multiple systems. I use 1 inch, micro four thirds, and full frame for different situations and purposes. I’ve managed to avoid medium format but the price of Fuji gear makes it tempting to try it. I use a smart phone to capture a wine label etc. but seldom for photography. In the end it’s the shot that counts and most people don’t even notice minor technical deficiencies. A big deal to me is what cameras and lenses I enjoy shooting and what I’m willing to carry.

Not if you know what you’re using them for. And yes, the image should be good enough or purpose clear enough that the technical stuff is secondary. That said, one’s choice of technical properties should also be commensurate with the image intention…

Very, very interesting paper Ming, thanks… If I understood correctly, in terms of images produced, the differences between digital sensor formats are pretty similar to the differences between different film formats.

Eventually we’ll get to that point, yes – when photo sites are pretty much homogeneous across the board and larger sensors just equals more of them…we are getting to that point, I think.

Great article. One thing that is starting to blur the lines between different formats, particularly at the smaller end, is computational photography. The ability of small sensor phones to use multiple lenses to composite an image with apparent good separation between subject and background, and the excellent in-camera focus stacking of Olympus TG and m43 cameras to increase the apparent depth of field without going past the diffraction limits are potentially game changers.

This has just started, and improvements in the near future will be interesting to watch.

It’s early days, but yes – the previous direct optical/physical relationship between DOF and format size is no longer to be taken for granted. The transitions and edges are messy, but that will only improve.

Beyond focus stacking I’d also add HDR and sensor-shift resolution increases, but that’s a whole separate topic for future discussion…

Agreed. I have been very impressed with the HDR mode in the Ricoh GRIII to increase DR. It seems to use a single RAW file and process it to produce, in most cases, a very natural looking HDR jpeg. No need for alignment of multiple shots as used by Olympus cameras.

…which is pretty much what we’ve been doing with RAW workflow thus far – though inexplicably it’s taken a long time for them to figure out how to do this in camera…

Great article – cuts through all the format-war twaddle with cool reality 🙂

I will stick with M4/3″ and hope that sensor development will eventually give me a stop or two more in dynamic range, which is the only irritation for me personally – I often have to sacrifice 1 stop to avoid highlight clipping, and sometimes two. This is mitigated somewhat with good shadow recovery though.

Paul

You actually give up less than you think because of stabilizer effectiveness – with M4/3 I usually find myself at lower ISOs than larger formats.

Good point. The ability to use lower shutter speeds and/or larger apertures while maintaining DoF does improve light gathering.

My issue is usually in bright sunlight, where I find it necessary to dial down exposure more than I would like to avoid clipping highlights. Fortunately the low ISO does allow 3 stops or so of clean shadow recovery though, but jpeg previews are a challenge! Now if I could use S-OVF with accurate blinkies or live histogram that would help.. Sadly on my EM-10 II that does not seem possible.

There is the shadow push option though – Olympus does this quite well with its jpegs.

Thanks for your thoughts on this, Ming.

When I shot with film I used both 6×6 and 35mm (and 5×4 for specific tasks.) Whilst I couldn’t explain why at the time, I was noticing differences in the way the subjects were rendered between the two formats, and as I did my own D&P I always favoured 6×6. There was the depth separation you talk about here with the 6×6, and although I would use the same framing artifices with both formats to try and achieve a 3D effect, I couldn’t achieve the same result with 35mm. As I could readily see this with 6×6, why the difference has always puzzled me, until now.

You can get it with 35mm but it requires highly corrected and fast lenses. It’s generally easier to make highly corrected slower and longer lenses (i.e. for lager formats) than faster and wider ones. I’ve seen the same kind of MF-style 3D separation on 35mm film but only when shooting with the Otuses (and even then it’s been a while). I suspect that smaller format film also hides a multitude of errors to do with focusing, lens corrections etc. due to lower resolution…

The last time you wrote an article about the pros and cons of different formats, you ask your readers what two or three formats they would prefer to use. At the time I started my preference for micro 4:3 and the 35mm FF formats. At the time, you were of the opinion that micro 4:3 was easier to use for macro/close up work. With the release of the Nikon mirrorless system, do you still hold this opinion? Granted, one probably had to adapt existing 35mm FF macro lenses to camera bodies like the Z7 to evaluate the relative ease of use compared to, say, the Olympus 60mm macro on a micro 4:3 body in order to formulate a definitive opinion. However, are you prepared to even guess as to whether a 35mm FF mirrorless system would surpass that of a micro 4:3 system in the macro and close up genre?

My opinion on ease of macro production is based mainly on sensor size – this doesn’t change with the Z cameras. It is a bit easier to do tilt shift macro since the finder is now WYSIWYG, but the DOF advantage still Liles with M4/3. Image quality is of course something else entirely.