…or, ‘statement of underlying principles and philosophies as relates to the way MT sees and captures the world’ – but that doesn’t quite read as smoothly.

We all start our photographic journeys with the intent and desire to capture something specific; we may or may not succeed at this to a level with which we are happy. Inevitably, the next step is to attempt to capture everything, almost indiscriminately; if done well, this produces a curation nightmare: the gates are open and we are now seeing opportunity everywhere. We may or may not (likely not) have the executional skill required to translate that vision into an image that is read as intended by our audience; we may not even know who the audience is yet. Fast forward through the GAS, and if you make it that far – the hard road is only beginning. Rapidly diminishing returns set in and serious dedication and practice are required to make any meaningful progress; the hardest part of which is developing an objective yet fair ability to self-critique one’s own work. Previously, I’ve detailed this process in the stages of creative evolution; I’ve discussed general underlying motivations for photography here, here and here (and probably elsewhere that doesn’t immediately come to mind). What I’ve not done much of is talk about why I personally photograph what I photograph now. Sure, it’s probably possible to form an overall picture of my philosophy if you’ve read enough of my articles, and there’s a massively antiquated raison d’être of sorts on my flickr profile – but as we change, so do our motivations. Or vice versa. And that complex balance is what I’m going to attempt to explain today. The overall picture may well diverge from your own approach, but hopefully some of the individual points might be useful.

Important note: notice none of the tenets is subject or location specific (let alone hardware-dependent). A consistent and solid approach needs to be as universally applicable as possible.

1. Observation

You cannot capture what you cannot see, and you cannot see if you are not continually observant and receptive to input. This becomes especially difficult in a familiar environment because our minds tend to work to block our repeated stimuli – otherwise we would never get anything done. It actually requires a considerable amount of mental training to undo this and ‘open your eyes’ again. Bottom line: creativity is derivative, and the inspiration has to start from somewhere: it is never internal; we are responding consciously or subconsciously to our surroundings and must therefore have input to act. The more input, the wider the possibilities.

2. ‘Idea priority’

Observation complete, idea germinated, it is important to ensure that the core essence of that idea survives execution (making into a photograph) and translation (understanding of the intended message through the photograph by the audience). Everything else is secondary, even if it might not seem that way to others, with the most frequent two examples being a) acquisition of hardware with a very specific purpose being misconstrued for GAS, and b) a perceived mismatch between quantity of ancillary hardware and outcome (“that’s all you use? two bits of cardboard and a flash?!” “why do you need four flashes?”)

3. Immediacy and intuitiveness

The corollary to sustained observation is gut feel: we need to learn not to ignore things that trigger an initial response of some sort. That initial response transcends the rational mind to some degree: an emotion is triggered before we have a chance to understand and rationalise what we’re looking at. Given all images need to have an emotional component to be memorable, it therefore makes sense to build on the triggering element as a starting point. Similarly, it’s possible to overthink an image and make it too clinical by removing or deliberately excluding too much of the surrounding context; I firmly believe we observe things on both conscious and unconscious levels, and what we unconsciously notice and/or want to include tends to have some tangible bearing on the overall mood and feel of the image. I try to strike the fine balance between between eliminating anything obviously distracting at first or second glance, but leaving in enough visual texture to preserve authenticity.

4. Fidelity

This principle could also be read as ‘realism’: in essence, what elements or presentation methods contribute to the believability of the idea contained in the photograph? What do I need to include to avoid triggering the initial reaction that ‘this must be photoshopped/ CG/ staged’? A photograph has to look like reality: that is, you do not question if the elements contained within physically exist or not. However, it may look as though their presentation or positioning is impossible or improbable – in fact, I find this desirable in many ways.

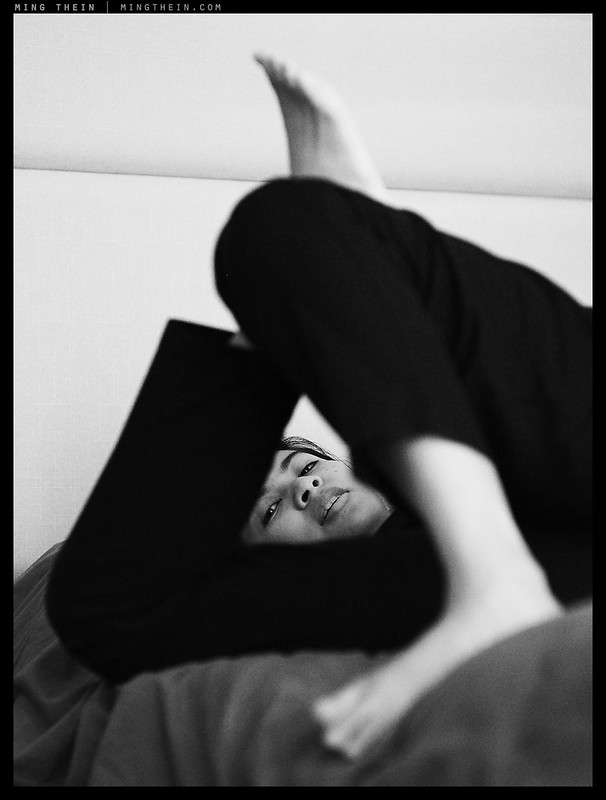

5. Spatial dissonance

When something appears to contravene natural laws or expectations, it grabs your attention, meaning you stop and look: precisely the desired outcome for a photograph. The longer it takes the audience to figure out what’s going on, the longer they have to spend time consciously viewing and evaluating the image to try and understand it. This means a greater opportunity to present the idea, in a clearer, more specific (detailed) form – and a higher chance of being remembered. At a higher level, if the purpose of a photograph is to identify, communicate and preserve the unexpected or unobserved: surely a scene that must obey natural laws (since a photograph is expected to be a faithful representation of physical reality) but appears to do the opposite is a worthy subject?

6. Layering

Once that initial grab factor wears off, there has to be enough visual texture and depth in an image to hold your attention and keep you looking, beyond providing sufficient detail for plausibility. A one-dimensional scene does not hold attention for long, because there is no ambiguity: every visible element is fully represented and nothing is left to the imagination. There is no suggestion of undiscovered potential, no implied spatial order, and no feelings of intimacy of distance.

7. Deliberate ambiguity

As specific and literal as a photograph is – the challenge is to leave some part of it up to the interpretation of the audience. It is impossible to make an image that references only a universal set of visual cues such that every possible viewer reads it correctly; there are always going to be some locally contextual items that have no meaning outside a specific group. But if some less critical or distinguishing elements are omitted, obscured or obfuscated, then the applicability (really, believability through self-projection or imagination) is much broader – thus, widening the impact.

8. Structure and balance

Or, read this as ‘ordered complexity’, ‘intricacy’ or ‘wimmelbild‘. It is the underlying framework over which the elements must be overlaid; both spatial structure in the real world and visual structure in the photographic one. One of the great strengths of photography is though it is based on the rules of the physical world, we have the ability to distort the order of visual priority through manipulations of perspective and light; largest may not be boldest and therefore not immediately noticed – and vice versa. This allows a lot of flexibility when prioritising reading of elements, which in turn implies an order of causality, a relationship, and a story.

9. Unconscious suggestion

Though it is good to be able to present subjects in such a way as to be immediately noticeable, it is better still to have other elements register at a subconscious level to set the scene – I think of this as the visual analogy to the props that are carefully selected for a movie scene, or the quality of light, sounds and smells that make a place ‘authentic’. It requires the photographer to observe at a level deeper than the audience, and deliberately include and guard those very nebulous elements so they remain intact and noticeable enough…but not too noticeable.

10. Consistency of presentation

I think of this as a trait that extends beyond mere post processing, color tone or aspect ratio; it is possible to have very fixed expectations of perspective, quality of light, color palette etc. but yet a highly diverse output: note that the subject remains independent. Images must be able to work together as a body of work without being jarringly disparate, strong enough to be viewed in isolation, and yet different enough not to feel like photocopies of each other. I find the best way to approach this is to split the process into several parts: originating and capturing the idea; conceptualising the output; curation, and then final presentation. Minor adjustment might be needed between curation and final presentation for consistency, but if the processing has to be changed so dramatically – the idea might not survive intact, and we have a self-selecting curation event.

I realise that most of these principles might seem contradictory at first glance. There is definitely a certain underlying tension between them, and an art to balancing them (sometimes very much intangible and difficult to explain) in a way that creates an image I consider ‘mine’ and that could not have been made by anybody else. In fact, that’s probably one of my curation criteria: if it could have been shot by anybody, then I’m not trying hard enough. What it means in reality is that there’s a lot of experimentation (still) as you exhaust all possible executions of familiar subjects; a significantly lower output rate with time, and an increasingly narrow (but more sympathetic) audience that fully ‘gets’ your vision as that very same vision sharpens. I have the luxury of being able to make the images that my clients want, for my clients (which are somewhat locked into a self-selecting loop by the images I choose to present); but I also have the luxury of choosing to make images that satisfy me, and in the long run: I need to be happy with my work. This becomes an increasingly frustrating and low-yield process the further you go, but when you make something you’re happy with – the sense of satisfaction is also higher. MT

__________________

Visit the Teaching Store to up your photographic game – including workshop videos, and the individual Email School of Photography. You can also support the site by purchasing from B&H and Amazon – thanks!

We are also on Facebook and there is a curated reader Flickr pool.

Images and content copyright Ming Thein | mingthein.com 2012 onwards unless otherwise stated. All rights reserved

Looking at these photographs and reading the text I’m wondering if you in your experiments and developments ever tried, for an extended period of time. To take even, static, plain and deadpan photographs but avoiding the obvious styles? Finding the furthermost diffuse edges, rather than polishing the focused core, of photography.

With any luck you understand my comment despite what it is.

No, because it doesn’t interest me.

First I want to thank you very much for this wonderfull text and very descriptive photos.

The photos raised my question: how and where do you name and file your pictures which very often show and transport much more than the merely depiction of the objects or subjects. And I’m quite sure your file stock is very extensive.

You hardly could name your photos just “chairs, kitchen, facades, reflections” or something like that. In other words: how do you describe and file the more important content of your pictures which is often more related to the meta-level?

Titling – is a whole separate subject covered here.

As for organisation and filing – I have subject/job at the first level, and then chronology at the next level (depends on how much volume there is as to whether it’s monthly or annually). Each camera has a unique identifier and file numbers are sequential, so there are no duplicates. I’ll pull out a highlights reel of images I feel are exceptional every month, and that’s filed accordingly. This is generally enough to get folders down to under 1000 images, at which point you can easily browse thumbnails to find what you need. Hope this helps!

I always enjoy your reflections. I’m interested in what holds attention for more prolonged viewing (like ambiguity which you mention). One thing may be whatever it is about the photo that keeps the eyes moving around the picture. I’m also pleased when my photographs have emotional impact like when my grandaughter’s ballet teacher said she cried when she got home and viewed the prints I had given her.

For me the subject influences how conscious and intellectual the process of taking a picture is.

While I may have story boarded in advance (at least mentally) the shots I would like to get at a fast moving event or sport, the actual shooting becomes more intuitive. The conscious questions get narrowed down to light, background clutter or context, and anticipating ‘the moment’.

With more static subjects, it often starts out more intuitive (something catches my attention) and then the actual shooting becomes more intellectual and question posing. Why did I stop to look? What is the story? What is the best angle and frame? Would backlight be more interesting? Is there really a photograph here that I might hang on my wall or should I move on?

Thanks for sharing how you think about photography.

The subject also projects their own emotions into the image, which in itself adds another layer of engagement we cannot control directly – this will always be the case, unfortunately. It is not possible to be all things to all people.

Agreed on storyboarding: the risk is that you may walk past or not notice something interesting in itself, but tangential to the storyboard (I have this problem too). Yet of course one cannot be too distracted, either…

These items are so well reasoned and easily understood despite their complexity and subtlety. In order to do this, I suspect you are constantly asking yourself some pretty direct questions that require a lot of soul searching but above all honesty with yourself about how each step in your process is working for you. In order to answer those tough questions, you reason your way through them methodically in order to avoid previous pitfalls and achieve the quality output you desire. Is that the case?

I really value your writing and thank you sincerely for the generosity you show when you present them to us.

Many, many thanks.

Pretty much – either I get the image I want, or if not, try to figure out why not – the process has almost become automated in a way…

An interesting read.

This is not meant to sound accusatory at all – it’s just to get the discussion ball rolling – but do you consider that it’s possible to overthink these things? When we first get into photography and start taking photos for the sheer fun of it, I very much doubt that we get into this level of analytical introspection. I can see the argument from the other side – if you don’t think about what you’re doing, then you won’t understand why some things work and others don’t and you’ll never make any real progress. However, by looking at lots of art of all forms, we subconsciously pick up on things and then those things start appearing in our own photography – and we don’t always notice it until later. This strikes me as a more effortless way to keep our artistic journey on track.

I saw something on Japanese TV once (it wasn’t my fault, my wife had the TV on. Japanese TV is absolutely awful, as you may well be aware). They had two singers singing the same song, and they were using a computer program to measure how close their voices were to the “correct” pitch; the producers then proclaimed that a (notably Japanese) trashy R&B singer was “better” than a (notably foreign) trained opera singer. This kind of thing – attempting to scientifically analyze what are highly objective factors – is almost impossible for me to comprehend.

This might be a personality thing, too; some people are naturally inclined to be analytical, and others balk at the idea of trying to consciously work out why photo A looks good to them and photo B doesn’t. I’m very firmly in the latter camp.

Again, this certainly isn’t meant to sound like I’m calling your approach wrong. It clearly works very well for you. It’s just that I find it impossible to think about photography – and many other things – in the same way and I find it very interesting to read the ideas of someone who can.

Sorry – for objective, read subjective!

Absolutely. To just have fun – do what you enjoy. But to go further both professionally and artistically, I think we need to have some idea of our motivations and skills (and audience) to have the level of control necessary to say what we want. It’s like language, I suppose: you need to learn to read and write at some technical level before being able to wing it, but the more you wing it, the easier (and more intuitive it becomes) – until you want to be incisive and precise and need to start thinking all over again.

Japanese TV: there’s a little Japanese restaurant down the road I go to regularly that’s always playing something random on NHK. Yes, it’s awful, but with the sound off…oddly entertaining and adds to the ambience. One day, satellite wasn’t working and the place felt odd; we didn’t realise why until noticing the (always silent) TV was off. Did the owner use it to create ambience deliberately, or remind himself of home? Probably not; but at least I know if I wanted to recreate it (or wanted that feeling) I’d know what was missing. 🙂