I’ve struggled a bit for a title to today’s essay. Through the course of my investigation into other forms of art – perhaps investigation is a bit too strong a word; meandering or exploration is probably closer – I’ve noticed that photography stands apart for two reasons: perception, and origin. They’re really one and the same if you dig a bit deeper, and this also applies to a lesser extent to its derivatives – film/ video, mixed media etc. I suspect I may open a can of worms with this piece, but I’m also hoping it’s going to provoke some interesting discussion below the line in the manner of some of the classic posts of old…

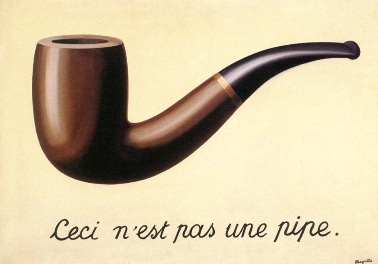

Let’s start with the simpler of the two: origin. Photography is what I think of as a secondary medium. For the most part, the output is a recreation or representation of something, where the something – the originating object, subject or scene – is clearly defined and recognisable in its original form. There is no attempt to suggest that a photograph is anything other than a facsimile of the scene, with adjustments for the bias of the observer – the photographer. Let’s take the example of an apple: if you paint it, no matter what you do, you’re not going to paint it exactly the same; even if you try. And you’re probably going to paint the idealised idea of an apple, not an apple itself: the artwork that comes to mind is Rene Magritte’s ‘this is not a pipe – the treachery of images’ (which is itself a photorealistic painting). It is a representation of what the artist believes that object should look like, the sum of his or her expectations. Not the object itself.

Treachery of Images by Rene Magritte, image from Wikipedia. I’ve been lucky enough to see this painting in person, and it’s both small and unassuming – it doesn’t have very strong visual impact, but give it a moment to register and you’ll see just how successfully Magritte transcended the limits of the medium and painted not a picture of a pipe, the idealised representation of a pipe, but an idea.

No matter how much a photograph uses technique or light or exclusion, it will still be recognised and – this is the important bit – interpreted by the audience – as being a representation of that specific object. Though this may be generalised to type – a photograph of ‘a rose’ as opposed to ‘the rose’, for instance – for the most part, photography is very specific in its depiction. Other forms of art are not, because the interpretative filter of the artist is opaque – not translucent. This distinction is perhaps best made through that of light itself: in a photograph, light from the object passes directly to the recording medium (and for arguments’ sake, the final output). What the photographer sees is what the camera sees. In a painting, it must first pass through the eyes of the artist, the interpretation of their brain and motor skills, and then only to canvas or sculpture or whatever media happens to be their choice.

Recognizability of the subjects within a photograph drives perception of the audience: it looks like the subject, therefore it is. It is not always recognised as being an artist’s interpretation – perhaps that is the fault of the artist for failing to see their own vision in the subject or scene, or perhaps it is their lack of technical chops in the execution. Whatever the case may be, few photographs are mistaken for anything but photographs. This has two consequences on the art itself: firstly, the perception of an image that is not instantly identifiable as a photograph may confuse the audience, but it may just as likely surprise and engage them for its difference; secondly, the commercial value of a photograph no doubt takes a beating.

Even though we have seen stupendously expensive photographs – Gursky’s Rhein III, for instance – in recent times, we still think ‘that’s expensive, for a photograph.’ It is still significantly less than say the value of a decent Monet. Undoubtedly reproducibility has something to do with it: the artist could simply make a copy, if we so chose. That wouldn’t halve the value of each image, it would lower it by significantly more, owing to exclusivity and so on. More prints beyond that lower value further still, but I think there does come to a point where you are better off making more copies at a lower price than fewer at a higher one. That said, I personally believe the ceiling for the value of a photograph is heavily influenced by people believing they could not only do the same themselves, but probably do it better. Certainly the artistic merit of the output is subjective, and the result may well be better in their eyes. But will it be exactly the same? That is unlikely, because every image captures a moment in time that is never to be repeated (in our lifetimes, at least). Even in a studio situation where the scene is fully within the control of the photographer and repeatable, there are entropic changes happening at smaller scales than we can resolve: invisible on the short term, but nevertheless still present.

I think the biggest hurdle photographs face is that the creation simply appears to be ‘too easy’ to the layperson compared to a painting (or sculpture, or carving, or any other medium). Most people harbour memories of painting from primary school and wince slightly at how poor the output looked; however, modern camera phones and general lack of visual education mean that pretty much everything is acceptable – and the difference between outstanding and great, great and good, good and acceptable, acceptable and mediocre isn’t always apparent. A painting takes time, paint and canvas, or whatever other media the artist chooses to work with*. Never mind the fact that it requires just as much time to master photography, the equipment cost may well be significantly higher, and I don’t think many people manage to output what they intend – the perception is there.

*I use painting as a continued example throughout this essay because it’s an easy analog to relate to since it’s visual and two dimensional; the same could well apply to any other choice of medium.

Conceptually, photographers have to be aware of the fact that the medium is one of conscious exclusion, not conscious inclusion. Every single act of framing is one of isolating out and discarding the bits of the work which are not relevant or interesting to the idea; this is the complete opposite to say painting or drawing, where everything that is visible in the final artwork has to be created by the artist – therefore they will have had no choice but to decide what form those objects or elements are to take. This is not the case for photography; the danger is that a photographer simply ignores the less prominent parts of the frame and lets them slide so long as they are not distracting. This is a mistake because it is coherence even through the smallest details that makes the difference between an excellent image and a truly outstanding one. I don’t think one method is necessarily easier than the other: the task of creating something entirely from scratch down to the smallest details is probably just as onerous as deciding whether each and every single element in a found scene is relevant or not, and how relevant.

There is of course a middle ground, formed of two types of photography that aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive. I’m referring to still life (or general studio/ controlled environment work)n and abstraction. In the former case, the scene has the potential of being fully within the control of the photographer, and the image made repeatable and tuneable; the latter removes the instant identifiability of the donor subject from the photograph and therefore prevents it from being instantly recognisable as one. Though in controlled environments the photographer is generally in control, they are probably not in control to the same extent as the painter: you may want an orange, but you can’t decide exactly which shade of orange and how many dimples it has in its skin – you can pick from a selection, but that is finite. The painter has no such constraints. Similarly, it’s much easier for the photographer to use strict perspective and depth of field controls to emphasize or de-emphasise elements in a scene; the painter can do it too, but it’s much more difficult to replicate convincingly. And if you’re a sculptor or mixed media artist, you’ve got the added consideration of physical viewing point to take into account, too.

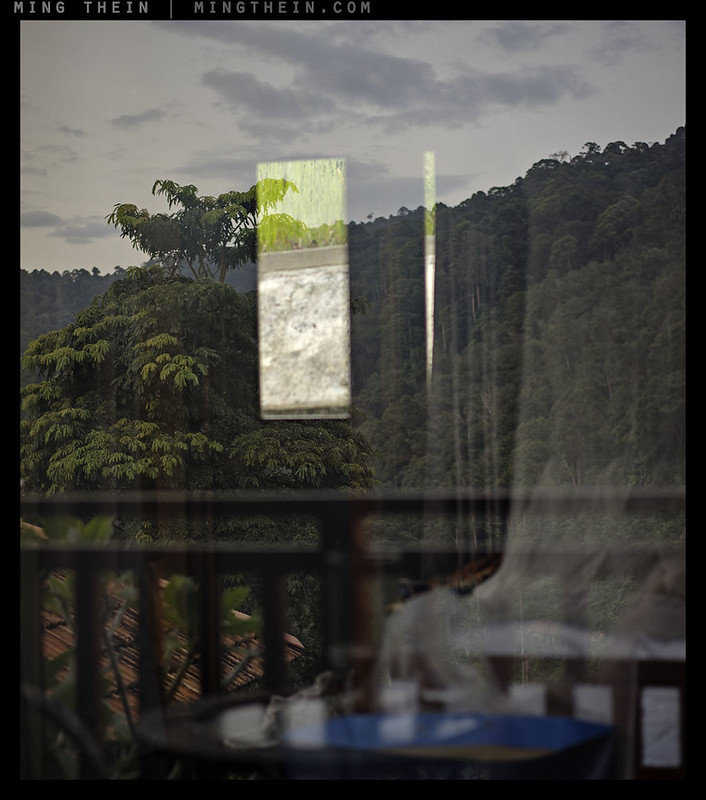

This is where I think controlled abstraction is an opportunity to raise photography to another level – to some extent it still has to be serendipitous or found as the photograph depends on the donor subject, but here the strength of the photographer’s interpretation can be made to clearly dominate over the subject. It can be done through perspective, scale, physical proximity/ magnification, removal of depth cues, certain lighting, reflection, or any one of many other ways. However, if certain specific visual cues are removed or carefully controlled – quality of light, color palette, depth of field, final reproduction medium – then it may not be entirely clear at all whether it is a photograph or not to begin with. Such photographs transcend both the medium and more importantly, the audience’s expectations of the medium. Sadly, they are not at all easy to execute.

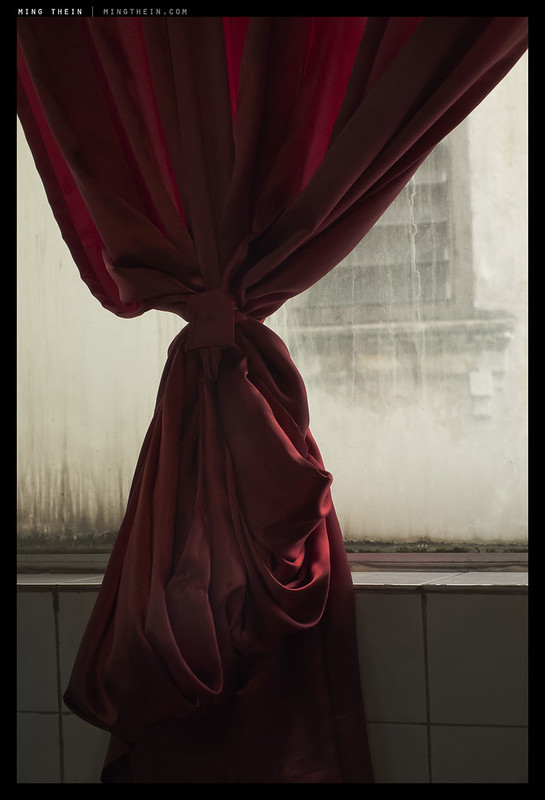

We must also consider of course that not every photographer wants to transcend the medium; a lot of they time they just want to make faithful, interesting, storytelling or client-satisfying photographs. I personally find the idea of transparency and the idea of making the photograph merely a conduit into a hyperrealistic representation of that instant in time and space very interesting too – hence my development of the Ultraprints. But for those who do – and sometimes that includes me, too – keeping in mind the ideas of conscious inclusion vs exclusion, questioning whether every single small element in a scene is necessary, nice to have, neutral or distracting, and thinking about abstraction – some very interesting results can happen. I believe the images in this essay are a good example of that; some of them consciously seek abstraction; some attempt to replicate the visual cues of a painting; others are simply an unusual perspective. Regardless of which, I personally find them visually interesting – compelling – because they don’t always immediately read as photographs, or if they do, they force the viewer to pause and contemplate a little. And isn’t that what any art form is about? MT

__________________

Limited edition Ultraprints of these images and others are available from mingthein.gallery

__________________

Visit the Teaching Store to up your photographic game – including workshop and Photoshop Workflow videos and the customized Email School of Photography; or go mobile with the Photography Compendium for iPad. You can also get your gear from B&H and Amazon. Prices are the same as normal, however a small portion of your purchase value is referred back to me. Thanks!

Don’t forget to like us on Facebook and join the reader Flickr group!

Images and content copyright Ming Thein | mingthein.com 2012 onwards. All rights reserved

.As there are so many applications to photography from speeding cameras to fine art, there exists a point in photography where it is at its purest point. It is not fine art and it is not practical, it is only photography. Your images above are examples of that point. Pure photography. I don’t consider what I make art, nor do I label it or intend it to be so. Yet I find that the “Art” label is harder to avoid that I thought. People will tell you its Art and disagree when I tell them its not. Sigh……

You know it’s at that point when there is no commercial application whatsoever and the cat-herding trolls can’t understand it 😉

That’s when its at its best point in my opinion

True! But oh so unsustainable.

Unless you call it “Art”. Then you might have a shot 😛

…and an immediate response:

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/dec/11/photography-is-art-sean-ohagan-jonathan-jones?CMP=fb_gu

The final word in this discussion? I don’t think so…

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2014/dec/10/most-expensive-photograph-ever-hackneyed-tasteless?CMP=fb_gu

I think the amount is rather surprising, but as usual I withhold judgement until I see a print. But he may well have been forced to eat his hat 🙂

Your thoughts on photography are on point! It’s almost like I’m reading a Jeff Wall article, sans the impractical writing style. I particularly liked the bit on figuring out a way of transcending the medium. I think it becomes problematic when we talk about photographs in a digital format, which is easily digestable and overlooked. An image’s impact is very different when it’s intangible on the screen versus the physicality of a print. You’ve mentioned it time and time again, but what I think photographers (particularly those who are trying to use the medium as an exploration of creativity) have to see their images in print and try installing them; little things such as the viewer’s surroundings, the space and sequence of the photographs, and being forced to confront an image in physical space causes one to look more critically at the process, details, and meaning of the photograph.

-G

🙂

Nice article. I agree that photography is different from other art forms but in general I think the differences are less about the medium, form of presentation (re-presentation), price, etc… The differences perhaps have more to do with the executioners – how photographers differ form other artists…

I enjoy your site!

“What the photographer sees is what the camera sees.”

https://www.lensculture.com/articles/chris-mccaw-sunburn

Probably the most extreme example. Long time exposures are a realm few attempt. Despite the really long time commitment, the results are also not easy to predict. Our eyes see a small time slice of light at any moment, though the camera can accumulate light for a very long time, in a way our eyes and mind do not easily imagine. Anyway, I got your point with that segment, and that one particular sentence should not be taken literally. We still know that McCaw’s images are photographs, even if the results are not easy to understand without some explanation of his technique.

I completed my art degree with an emphasis in painting, then started off professionally doing commercial illustration work. Images could be rendered realistic, representational, surrealistic, or abstract. There is more flexibility in drawing and painting, though those four things are possible in photography too. When I had photography classes at university, I had the great fortune to have a professor who pushed us beyond realistic and representational. A photographic print is a photographic print, and today most people think it was just done in Photoshop, if they don’t easily grasp an image. Printing a photograph on canvas doesn’t make it a painting (I’ll probably catch some flack for saying that 😉 ).

Graphic Designer David Carson put together a book years ago called “Fotografiks” that questions much about imaging. “Photographs with a very low level of information cause us to be more aware of the visual character of the image. Color, shape, and space come to the fore as content recedes.” He’s a bit of a controversial designer, in that people either really like what he does, or really hate it, living few in the middle ground. Most of the images in Fotografiks are surreal or abstract, until you read the text accompanying them. I think it’s good to question photography, on more than just an obvious level. Often we can learn from the things we dislike, as much as we can from things we like.

The one are of photography I have never attempted is pinhole photography. These great modern tools we use are so precise, it seems it would be frustrating to step back to the imprecision of pinhole photography. Then I look at images by artists like Vera Lutter. 🙂

Good points, Gordon. Perhaps I should have been clearer with that statement: the camera sees only what the photographer imagines…we can ‘see’ things that are beyond the literal. Long exposures, as you point out, are a very good example. Postprocessing of any kind is another. And monochrome images are the most obvious.

Well written and thought provoking article, Mr Ming! I like the fact that you are now writing about abstract photography also.

Thanks Bjorn. I’ve been doing it for a while, but never been fully able to explain why it appeals…

Well written! Thank you, Ming. To me the crux, or one of them, is that photography (except 3D photos or movies with those special, weird glasses) is intrinsically 2-dimensional while visual reality is 3. Photography is not mathematics where 3 goes into 2 X number of times. Thus it’s very subjective, not objective. Our visual perception is a wily trickster. And a thoroughly enjoyable one, no?

Absolutely. That projection or conversion of 3D into 2D can be interpreted in so many ways – the most interesting and enjoyable ones are the nonlinear and nonintuitive ones…

Hi, only a moment to write.

I will have o quote a line or two of yours in my research paper this week.

I take a course called UST499 in still photography; I am a student.

Anything I write would be too esoteric. No thought of mine makes any sense. Here goes; oh well. I think lately of “worlds.” My phase right now is that there is no world. The world singular does not exist in any comprehensible form. It would be like trying to really understand an number like, let’s say, 7 billion. What I see instead are tiny worlds. By that I don’t mean macro or microscopic, but small interactions. In way I see photography as different, maybe, strangely, harder than painting…

It would be like telling someone you love I have soothing special to say. Then ask what it is. Then you hand them an entire set of encyclopedias. Even one page of an encyclopedia is too much. So I guess I mean that the photographer captures small worlds; a mom and her baby, a staircase, a window, one tree alone, a gaze, and so on.

I hope this added something.

Best, jw

Visual and written/spoken language are simply incompatible and incompletely overlapping. It’s a good thing we don’t have to choose 🙂

Monsieur Ming. If you really got the message of Margritte pipe, you would rather call your first picture “This is not a red drape” , if you get what I mean. Please don´t take as a unconstructive critisism but you do have a tendency calling apples for apples with you picture titles. Regards

I really get it. But I choose not to rename images I’ve previously named for consistency of reference.

But the camera has not a brain. It is the photographer the one that first see the image and then press the shutter. I can’t see what you are seeing.

I’ve always said to my students that photography is about learning to see; the rest is just technical capture. Without the former, the latter is meaningless.

Again, you’ve managed to write an interesting and stimulating piece that I will be sharing with others. Thank you. I feel that I learn something about the world and myself, not just photography, in nearly every article you post, as well as in the comments from your thoughtful readers. It’s creating a more interesting journey, thanks to your probing curiosity and camera work. I enjoy the way you intertwine your work/images with your words/thoughts.

Thanks!

Great article as usual!

I would like to recommend a few books that are rather arcane but from an era when differentiation of photography as fine art was a primary concern: pictorialism (late 1800s to early 1900s). They offer a slightly different perspective than photography publications of today dominated by “modernism”. (They also offer insight into the limitations of the technology back then but that’s not the subject of the post.)

All of them are freely available through archive.org (top left search field) as not under copyright anymore or can be ordered from Amazon as reprint.

1, Arthur Hammond: Pictorial composition in photography (some release at 1920, first possibly earlier)

2, Henry Turner Bailey: Photography and fine art (some release at 1915, first possibly earlier)

3, Henry Peach Robinson: Pictorial Effect in Photography: Being Hints on Composition and Chiaro-Oscuro for Photographers (1892)

1, Is a good general read about pictorialist aesthetic considerations and abstraction tools in photography like using uncorrected non-anastigmat lenses and textured papers…etc and tips in dealing with various subject types (portrait, landscape, groups, people in a landscape…etc).

2, Also offers interesting insight of the development of a photographer, the first excitement of happy snapping (mind you with a large format) moving onto the technical admiration of sharpness (sounds familiar?) to differentiating a view from an illustration and then reaching to making pictures. I found it an exciting read.

3, Is a little long winded (or maybe I just got tired, felt a little repetitive after the first two) and clearly based on texts aimed at painters of the same era (see Dover Art Instruction on amazon) but cutting out the things not under photographic command like edge control or overly constructed compositions (dynamic balance…etc).

It’s a shame today’s publications don’t go in this kind of detail anymore but rather lather rinse repeat the same old (new). Even if they read a little poetical today.

Fantastic – thank you! I shall look for those. Today’s publications tend to cater to what sells – sadly far too many of the ‘D5000 for dummies’ genre and not enough about the philosophy and reasons why.

The way you frame the problem arises from seeing photography as basically a mimetic art. It is also, and perhaps primarily, a diegetic one. HCB is telling a story, however elliptically. Obviously true of photography’s cousin, cinema. Also, the camera sees differently than the human eye. One of the great lures of photography is its ability to make things visible that elude our organic seeing. For example: when a horse runs, do all its feet leave the ground at the same time? So is photography’s true subject the thing “captured” by the “shot?” Or is it the illusion of the capture of time itself? (These topics have a long an complex history, being articulated in great and ambiguous detail by Plato and Aristotle.)

It doesn’t have to be, but being mimetic is the strength of the medium. Of course one could make all sorts of arguments in favor of limitations breeding creativity…

Ming this is a cracking piece, beautifully illustrated I love the opening shot, inversion and the barrier oustanding.

Thanks!

Picasso !! “with a cam instead of a Feather ” !!!

I believe the lower value of fine art photographs in comparison to paintings is that a photographer is much more productive in comparison to a painter. Even the fastest working painters cannot match the speed of even the pickiest of photographers regardless of difficulty in capturing the right moment.

And, I believe a photo can be even more powerful than a painting in that small imperfections in the painting might distract the viewer. For example the photo that you put in the cover of your gallery (Tree and river) is your best work in my view; and one the the finest artwork (painting or photographs) that I have ever seen.

Kemal

Thank you. In general, I agree. However, there are slow photographers – hours for an exposure, going to location, finishing production – and fast painters. Van Gogh often painted several per day; there are fingerprints in the paint from careless handling as he rushed to put his mind to canvas…

Reblogged this on Scribbles and Snaps.

A photograph is and is not like a representational painting. What about elaborately constructed scenes that exist only to be photographed, or composites?

No thoughts on the latter; the former – well, yes, you can construct the scene, but are you going to build the objects in it solely for the purpose of the photograph too?

Check out ‘Dead troops talk’. I’m sure it was shot in a studio.

Will do.

Interesting article again, Ming! There is however one aspect that it would be interesting to hear your comments on, and that is the type of photography where the photographer not only finds/sees/excludes objects/nature, but where the photographer plays a more active role as a “director”, where the is a strong aspect of “mis-en-scene”, think of Annie Leibowitz or Helmut Newton, or a whole range of portrait photographers, and even advertising. In such cases the mis-en-scene can create surprise, a new form of “truth” not yet seen, the “essence” of a personality etc, where part of the art is not only in the photograph itself, but in the interplay with the persons, the scene, the idea. To some extent this can be said about photographing objects/nature, too, but in “directed” people photography it is a strong aspect, contributing to the notion of art in the finished product.

Any thoughts on this, Ming?

There’s a photographer whose name escapes me at the moment who’s known for choreographing very large scenes down to the last detail – to the point of adding snow, positioning props in distant windows etc. That role is less about the capture and more about the imagination/production; I’ve always thought of him as a director rather than a photographer. In essence it probably isn’t so far away from creating a movie…

Brilliant piece, Ming. Gregory Crewdson is that fellow who stages the elaborate scenes.

Yes! He’s the one. Thanks Joe!

Another nice post Ming. Don’t know if you follow The Guardian online but this article about why photographs should not be in galleries is interesting and sort of relevant http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2014/nov/13/why-photographs-dont-work-in-art-galleries

Thanks. That post has been making the rounds – to me it reads as something from somebody seeking attention through an extreme opinion. The author only shows his own ignorance.

For sure I agree with you there Ming. One of the best exhibitions I have ever been to was that of Henri Cartier Bresson in Scotland where seeing some of his images enlarged and framed which I’d only ever seen in books before was something else.

Books are something, prints are something else. Sadly there are few books which live up to good prints – it’s simply not commercially feasible.

Holding on works on so many levels. Brilliant – it is simple yet perplexing.

A small tangent: price and value are two extremely different things. The ‘value’ of an artist may only be recognised posthumously (van Gogh). In such a case they have succeeded as an artist at the cost of their livelihood. Conversely, the price an artist attracts might actually be priced above their value (Hirst?).

The art market is bizarre. The aesthetic experience of art and perhaps value, should have nothing to do with price. It is too subjective. A replica of any great artwork, an atom for atom copy, would be just as enjoyable as the original. The information it contains would be identical, yet it would be worth almost nothing.

The copy doesn’t even have to be exact. It merely has to be indistinguishable – like a Turing test for art:

“Even in a studio situation where the scene is fully within the control of the

photographer and repeatable, there are entropic changes happening at smaller

scales than we can resolve”

Does it matter if we cant resolve the entropic changes? Ascribing immeasurable properties to the object is like looking for a ghost in the machine.

A Turing test for art…now that’s interesting. We’ve had forgeries for years, some of which have passed the test – yet they’re still seen as forgeries. So there must be something else here…

I can only think of heritage? History? Authenticity?

I can’t help but be a little bit cheeky with this phrase: “few photographs are mistaken for anything but photographs”. How do you interpret photorealism/hyperrealism as an art form? It is an odd blend of passing through the eyes of the artist with an objective of producing a facsimile. Given a camera is often used, elements of inclusion and exclusion can apply. It is an interesting reaction to the invention of the camera…

I’m a big fan of hyperrealism, but that probably doesn’t surprise…

Ha! Not so much…

Your best yet for me. I found it a difficult read as I was constantly distracted by the fabulous images, but I got there in the end. An immersive experience. Great

Bill Spencer

Thanks!

It’s interesting that this post appears today, after I’ve spent most of this morning reading about and looking at the work of Minor White. He attempted, and sometimes succeeded, in his goal of having his photographs work on several levels, requiring the viewer to “fill in the meaning”. His photos were not merely photos of objects. I find his work to be abstract and also familiar. Any photography that can achieve this level of audience involvement is rare indeed, and undoubtably can be considered “art”. Your photo, The Barrier, approaches this. It’s very good. (I love the Magritte, too. It doesn’t shout at you).

I try 🙂

I think you are already there Ming!

Not yet – gotta sell more work!

Thought provoking and well done! I like abstraction and shooting abstract images.

Thanks Eric!