*Or, an example in construction series.

Like most photographers…I am not immune to the siren’s song of very fast lenses. And even less immune to the lure of lenses that are fast and designed to deliver performance at maximum aperture – think of the Zeiss Otus series, for instance. We’re even willing to compromise with older designs that perhaps don’t perform or resolve quite to the level we’ve come to expect from modern lenses on modern high resolution sensors, but write it off as being ‘characterful’ or ‘nostalgic’. Or even trying to rationalise that we don’t need such high resolution since most of the frame is out of focus anyway, plus we want a smooth transition between the bits that are and the bits that aren’t. And then we try to adapt lenses to systems they were never designed for (here, and here) – with varying degrees of success. However: the reality is we probably don’t need such tools the vast majority of the time, and even from a creative standpoint – a wider aperture doesn’t necessarily make an image better.

The reasons break down into the practical and the creative – let’s start with the simple stuff. All else being equal, cost and weight will take a significant hit, and there’s no guarantee performance will be higher. In fact, it’s much easier to design a highly corrected, moderate or slow aperture design than a faster one. And by the time you’re down a further stop or two – there’s not much difference. If anything, the fast lens might experience a drop off in performance as it was probably designed for wider aperture use. Practically, we might be talking 85/1.4 Otus vs AF-S 85/1.8 G vs 85/2.8 C/Y MMG – but by f5.6, there’s very little between them. The rest of the time, you’re just carrying around anywhere up to 800g of extra weight and 10x (or more) the cost*. As sexy as the Otus is, if I don’t need it – I’ll take the 85/2.8 C/Y MMG (and two other focal lengths for flexibility, all with less total weight). During daytime, especially in the brighter parts of the world – it’s easy to hit your camera’s maximum shutter speed limit; ‘sunny 16’ at ISO 100 (1/100s) means needing 1/12,800s with the same exposure at f1.4 – oops, time to break out the ND filters.

*Leica expresses this cost-heirachy-penalty best: at 50mm, in M mount, f0.95 costs $11,700; f1.4, $3,900; f2.0, $2,300; f2.4, $1,800. It’s almost exponential: is the extra stop from 1.4 to 0.95 worth $7,800? Probably not, and even then, you’d have to use it all the time to justify it. Cue the buyers’ remorse…

And this is before we even start to consider the performance penalties on things like AF systems: more weight = slower focusing, yet higher precision required as the focal plane is thinner and transitions between in and out of focus much more abrupt. Then there’s assembly tolerances and resolution: the higher the performance or faster, the more complex the design required for sufficient corrections, and the more likely something is to drift in that process. And yes, there’s often measurable performance variance even amongst very expensive lenses. In short: it’s practically much harder to hit the potential of a fast lens than you might think, and misses are exaggerated largely because of that shallow focal plane. We haven’t even considered things like focus shift yet – it’s quite common for noticeable focus shift as you stop down, though this is usually (largely) covered by the increase in depth of field, it may still yield unexpected results.

Practicalities aside, a fast lens is a bit of a one trick pony visually: the maximum impact is of course when used wide open with a near subject and distant background, or an interspersed foreground. Both background and foreground are rendered blurry and indistinct – cue discussions on bokeh, quality of, etc. which we shall not discuss here. Put simply: if everything is rendered out of focus and indistinct and (importantly) unidentifiable – then you lose a lot of the storytelling context that secondary subject elements can bring to a composition. You no longer know where a portrait was shot, for instance. You can’t see the looming axe murderer in the background, the incoming water balloon, or the surprise forum troll. It makes you blind to causal and narrative weaknesses because they are rendered invisible and thus, unconsidered. An image that says less is a weaker one. It might be immediately prettier, but not very satisfying on more careful viewing.

Here comes the dilemma: if you’re not going to use it wide open, then why have it? Granted, performance a bit stopped down will be better; for instance nobody would argue that an Otus at f2.8 isn’t better than a zoom wide open at f2.8, or f5.6, or your smaller aperture of choice. But really, by f5.6, f8 – the differences are vanishingly small compared to common mistakes in technique or post processing, to say nothing of the content of the image itself. Yet if you only use a lens wide open – then you’re a little limited creatively. Once everything turns into a wall of blur, you might as well have shot the same thing in a studio as the next person.

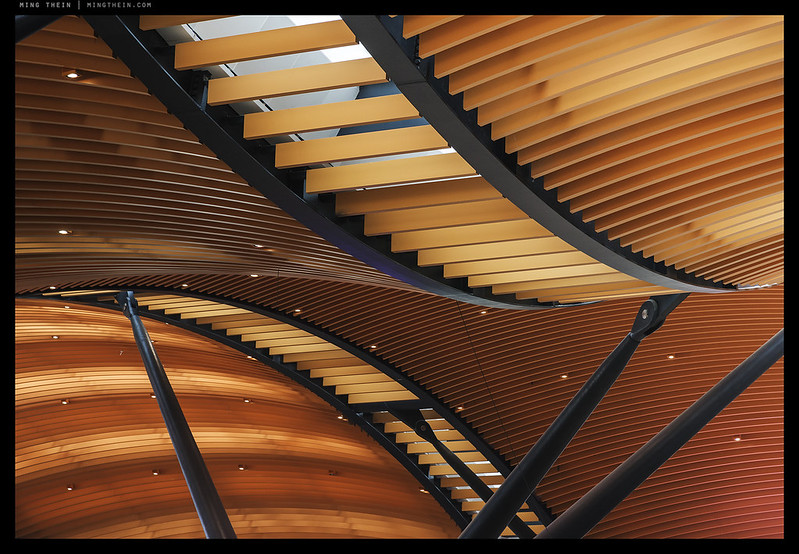

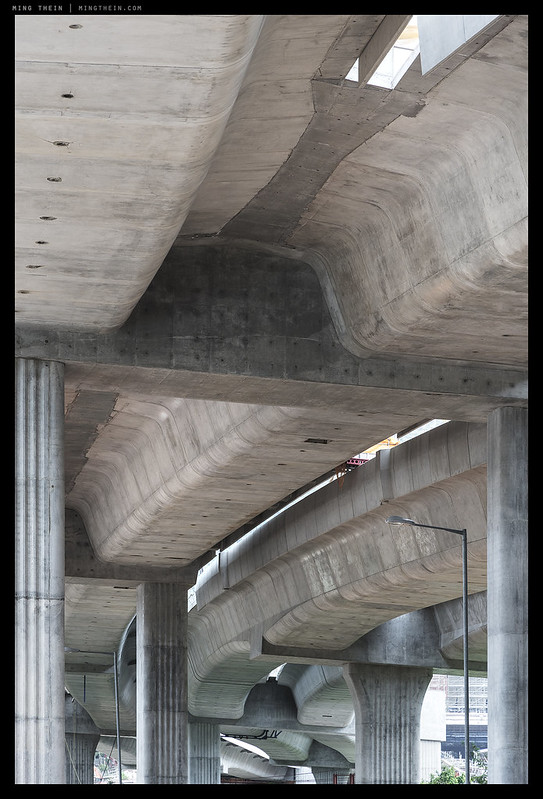

You can’t even deploy the difference under that great a variety of situations: a lot of commonly encountered scenes simply aren’t improved by separation by depth of field:

- If the subject and background or foreground are very close together

- If the subject is planar or flat (not enough DOF to cover), worse if orthogonal to the camera (DOF misses, field curvature etc. become very obvious)

- If the subject is very distant (resolution suffers, focus misses are obvious, at true infinity, everything is still in focus. Even very fast lenses have a hyperlocal distance, albeit very long)

- If the subject has tangible depth and you need that to identify it (e.g. complex 3D structures)

- If the perspective you need is very wide or very narrow; there aren’t that many ultrafast wides or ultrafast teles

- If your sensor gets smaller.

The last one is actually important, because we need to remember that the depth of field properties go with the real focal length of the lens used, not the aperture: for a 50mm-equivalent angle of view on say 645, you’re needing 80mm; on M4/3, 25mm. A rough rule of thumb is one sensor size = one stop to produce roughly the same apparent DOF, so your 25/0.95 on M4/3 looks visually similar to f4 on 645 – all else being equal. There may not be as much gain as you think.

However: there are two, (and only two that I can think of) situations where very fast lenses are justified creatively: firstly, when you absolutely don’t have enough light to handhold or freeze subject motion; that stop can make all the difference between crisp and identifiable or ‘creatively blurred’. The other situation really only applies to highly corrected fast lenses that have very distinct focal planes: the ability to separate objects from the background, but at greater distances. This means some background blurring, but just enough to tell that you intentionally put the focal plane somewhere else: it of course assumes you hit focus precisely and there’s a clean transition between in and out of focus. Background objects are still identifiable but not as prominent as the subject. But: if you’ve got a messy background, you still won’t be able to isolate a subject this way: the background won’t blur enough to create sufficient differentiation of texture. Rather it’s a bit of a layering bonus instead of a crutch.

I’ve deliberately picked the images for this post based on the most common scene structures I encounter (subject matter aside) – long planar subjects that recede into the distance and whose primary plane isn’t perpendicular to the camera sensor; complex 3D structures; perpendicular planar subjects at distance; convergent wide ‘cones’. In every case, the four things still apply: light is still paramount; subjects don’t isolate from similar backgrounds; underlying geometry directs the eye, and backgrounds are contextual and necessary to the story. Not one single one would be improved (read: achieve something closer to my creative intention at the time) by shallower depth of field; in fact, more would be better in several cases. Faster isn’t always better. MT

__________________

Visit the Teaching Store to up your photographic game – including workshop videos, and the individual Email School of Photography. You can also support the site by purchasing from B&H and Amazon – thanks!

We are also on Facebook and there is a curated reader Flickr pool.

Images and content copyright Ming Thein | mingthein.com 2012 onwards unless otherwise stated. All rights reserved

Hello Ming, Thank You for your post , wishing manufacturers were paying more attention to your noise-free blog and posts .

When I look at the (analog,35mm) original Olympus OM system , with its compact body and compact Zuiko F2 lenses (21,24,35);

I wish Mr Maitani’s spirit were reincarnated and brought back to the Olympus engineering team . Maybe a stop/turn back to the mega pixel race would allow to design lenses which are light and fast , instead of the current trend to mega pixel monsters cameras with huge and ultra fast lenses as Sigma (whose CEO has all my admiration for his business ethics), Olympus and now Canikon mirrorless (will) deliver . I read that the tiny Canon 50mm 1.8 and (old) 85mm 1.8 are in Canon’s list for supported lenses for their DS/R bodies so maybe it is all not impossible to design light/fast lenses between 20 and 85mm for cameras with a sensible /restrained megapixel sensor , such as Panasonic and Sony have designed for low light . And HCB could capture the decisive moment with his single mode Leica camera , so maybe we all do not need a machine gun sized like a big hammer to perform our task … Best from Brussels, Pierre

The hammers are only as good as their operators…

🙂

Hello,

You have just killed two birds with one stone:

If a photographer hangs around the same place long enough, something interesting is bound to happen.

There is no need to use modern super fast lenses for landscape shots.

The discussion that followed your essay has been quite enriching.

Greetings,

Henryk

P.S.

I took five photos of a mountain from the terrace of my apartment in the Swiss Alps.

Two shots were taken last week with Contax Zeiss C/Y 135/2.8.

I also photographed the same mountain in 2017, 2016 and 2015 with Contax Zeiss C/Y 85/1.4.

Any interest in seeing them?

Yep – that’s pretty much the conclusion I came to; patience definitely pays off bigger than a mad scramble.

All are welcome to embed images in the comments – it’s a photography site after all 🙂

For beginners reading this discussion:

When choosing camera/sensor-size and lenses, the main parameter defining the Depth of Field and the Blurriness of the for- and background is the *Diameter* of the aperture.

Or, more precisely, once you have decided on the Distance to your main subject and the Field of view, the distribution and size of Blur depends only on the *Diameter* of the aperture (regardless of the sensor-size & focal length combinstion) – as a good first approximation.

Except for close-ups!

[ Diameter = Focal length / f-number ]

Then the character and rendering of the lens also changes the appearance of the blurring.

– – –

Examples

for a chosen framing of a main subject

at different distances:

To keep the bokeh of a far background proportional to the close main subject,

keep the Aperture Diameter constant.

But:

To keep the background bokeh

proportional to the background,

keep (Aperture Diameter)*(Angle of view)

or, same thing, (F-number)/(Sensor size)

constant.

( Source: the Lens formula – for those who like math…)

How about the Sigma DN Art series of f:2.8 lenses,

19mm, 30mm and 60mm,

for M4/3 and Sony E?

( I’ven the 30 & 60mm praised by serious photographers.)

Never tried them – with M4/3 you get f1.8/1.7 in such small sizes and low prices anyway…

The Sigma 60/2.8 is unbelievable, just unbelievable… Near perfect at full aperture… for $200!!!

Sounds like it may be worth a look then…the only other M4/3 60mm I can think of is the Olympus macro, which is also excellent.

The number of replies, their various (even differing) views and preferences show that a really interesting topic has been opened which many of us care about.

Like others here, I appreciate the smaller, slower less expensive lenses. I’m also a fan of the Contax Zeiss C/Y line. I presently have the modest 50mm 1.7 and 28mm 2.8 (both MM versions). I used to have the 100mm 3.5 MM. It’s about the same size as the 85mm 2.8 and has excellent resolution. Ming, you make a good point regarding complex designs in faster lenses. More chances for issues to arise. I find that the older I get, the more I use smaller apertures. And if I’m mainly using f8 or f11, I’m not interested in the weight or cost of a 1.4.

Over the last year or so I have had a similar revelation. A few things that have lead me to this:

• I’ve gotten sick of big lenses. Especially on SLRs, I like the small lens/big camera feel.

• I find myself shooting somewhere round f8 for optical/DOF reasons

• That shallow DOF/ blurry background look has gotten really, really played outer the past few years.

It baffles me how high ISOs of cameras have only gotten better and better but lenses are getting faster and bigger. Those Sigma art lenses look rather nice, but f1.4 doesn’t interest me much and they are enormous. I wish more manufacturers would make some slower primes, like a redux of the Zeiss/Contax 2.8 primes. I wish we had a choice of slowish to fast lens in a range, as opposed to the fast to very very fast we have now (ahem, the new Nikon Z 58mm f.95…) or the just fast (Sigma).

From a photographic point of view, I often find that I used blurry backgrounds as a bit of crutch to avoid composing half the image. Sure, its more difficult to compose when you have to compose all of the elements clearly within the frame, but it is a more meaningful success when all of these elements come together without being merely blurred away.

Thing is, fast lenses don’t necessarily have to be that big: well corrected ones capable of supporting current camera resolution (and beyond) – do. And you can’t always buy an older design and stop down to make up for it – some aberrations simply don’t go away, or worse, you hit diffraction on smaller pixel pitch sensors very quickly; sometimes with effects visible even at f8 (M4/3, for instance).

The C/Y primes were a fantastic set of lenses, and still are. The good thing is they’ll also work just as well on most of the modern mirrorless stuff thanks to shorter flanges and adaptors 😉

Most manufacturers won’t do equal optical quality at different apertures because it simply costs too much – you’ll get one aperture/FL only at the high end, which tends to be the best overall design they can make (think MF, since overall volumes are not huge) or a slow economy version that also has economic optics, and an expensive fast one. To my knowledge the only manufacturer currently making fairly equal optical quality lenses across multiple apertures for a given focal length is Leica. And even then they have QC issues some of the time, and price issues all of the time…

The Zeiss C/Y are my favorite vintage lenses. Excellent almost all around. Even the zooms are fantastic (the 100-300mm is excellent). I like Leica R primes as well but prefer the draw and rendering of the Zeisses (sp?), plus equivalent lenses between the two systems tend to financially end up in favor of Zeiss.

Yes! I thought I was the only one who had a soft spot for the 100-300…the 85/2.8 is massively underrated, and the 35/2.8 PC is a bit of a unicorn if you get a good copy; there are too many out there with loose shift mechanisms and as a result decentered optics (and free tilt). I might pick up one of the other fast short teles to try like the 135 or 100, and I hear the 28/2.8 is also excellent…

The 85 2.8 is a fantastic lens. So is the 35 PC if you can get your hands on a good copy like you said.

The 100 Makro is excellent – a little bit of CA at lower apertures but clears up by f/8. The 135 is utterly outstanding. If I can’t afford to get a Milvus or ZF.2 I’m going to do a Leitax adaptation on one. I may just do that anyway and save money.

I will, however, recommend (for whatever my recommendation is worth) to stay away from the 180mm. It’s not bad by most lens standards, but it isn’t up to par in terms of the rest of the Zeiss C/Y lenses. Disappointingly soft until stopped down.

The 85/2.8’s strength is not so much resolution (though it has that in spades by f4-5.6), but drawing style. It has this smooth creaminess and interestingly cinematic flare properties that later aspherical designs struggle with…

Thanks for the tip on the 135. I have the ZF 2/135 APO, but it’s a beast of a lens and a bear to carry around, making something slower very attractive.

As for 180 – the only option in my book is the Voigtlander 180/4 APO…

All of the Zeiss C/Y lenses I’ve used have great draw. The 28 2.8 you mentioned is indeed excellent – a great (and much cheaper) alternative to the “Hollywood” f/2 version.

I have never used the ZF 135, so I didn’t even consider the weight. If that’s the case, I’ll definitely be saving some money and doing Leitax.

The Voigt 180 f/4 is one of my most desired lenses. I’m close to picking up the much more affordable 90 3.5, but the 180 is easily one of the top 5 most desired lenses on my list. Ahhh… gear lust…

The 2/28 ZF.2 is also optically identical to the ‘Hollywood’ – which is a much cheaper option, I think.

The 90/3.5 APO unfortunately isn’t as good as its longer brother – it just feels flat in rendering, rather than low-contrast-but-still-delicately-crispy. I sold mine; the 85/2.8 gets much more use.

The c/y 85 2,8 is outstanding, even on the Fuji GFX, I bought one after your recommendation, and to be honest I now own three of them. Unbelievable that Zeiss don’t offer it anymore.

Do you think the 2/28 will work well on the Z7, you stated once, that it’s not great on the Sonys, but they have very thick sensor cover glasses?

How well does the Otus 55 do on the Z7?

2/28: hard to say; I need to find another one to test. I only have the 28 Otus and 2.8/28 GR-LTM at present.

All of the Otuses are superb – even better than on the D850 because you can easily focus them now… 😉

Thank you, maybe I should have a closer look on the Ricoh 28 2,8 GR LTM.

I’m not so satisfied about what I have in the range about 28 and 35, although I got a lot of lenses.

My Sigma 35 1,4 Art shows massiv field couvature focussed at distance.

Sigma say, it’s within there tolerances…

My c/y 28 2,8 leitaxed to Nikon is quite weak in the right corner, maybe decentered.

The Distagon 2/35 is ok.

I also own the c/y 35 2,8 PC, but could just test it on a Fuji GFX, very soft wide open,

and very busy bokeh, maybe it suffers from issues you mentioned.

The GR 28 is a pretty bad lens optically, but the way it draws especially for monochrome…is something else. Lots of field curvature.

My CY 35 PC was one of the sharpest lenses I’ve used, tested on the A7RII – which has a higher pixel density than the GFX. I would imagine it shows soft corners when shifted on MF though, the image circle is large enough to cover 44×33 unshifted or with very minimal shift only.

I also had the C/Y 85 and Voigt 90 at the same time. The Voigt was a little crunchier in contrast, though it was refreshing to see that characteristic with high corrections for aberrations. Despite auto aperture, passing through EXIF and consequently focal length for IBIS, as well as turning the ‘right way’ in relation to the rest of my manual lenses, I still kept the 85. Size and weight being negligibly identical, this is a lens I kept for the rendering, though to the antithesis of this article, I feel a minor bump in justification for the ever so slightly aperture in edge cases like shooting film or reaching the sweet spot a little sooner, even though I know it’s really a moot point having committed to the notion of loving small, slower primes.

Fully agreed – didn’t do any harm that the Voigt was usefully faster and smaller, too.

…. or the Leica Apo 3,4/180

Can’t say I’ve used that one…

Ming what do you think about the rendering of 85/2.8 compared to the 85/1.4 zf.2? Pretty similar or different?

At comparable apertures, not that different; both use a spherical Sonnar design.

Try the Nikkor 180 2,8 AF-D. A light, sharp lens with great color rendition.

Is the C/Y 135 optically identical to the ZF.2? It’s a little tricky to know if things like coatings get updated or tiny tweaks make a difference or not, like claims of the Milvus being ever so slightly modified from the ZF.2.

The C/Y 135 is an f2.8, so it’s completely different to the f2 APO ZF.2 version.

Some Milvuses just have coating updates, some are all new.

The C/Y is f/2.8, not the same optics than 135/2.0

I love Contax Zeiss, and I have many (MM version). The best of all are the 85/2.8 and the 135/2.8. I took the same photos with different 135mm (Nikon, Pentax, Minolta), the Zeiss gave me a lot more details, and the colors are great too. Really excellent also are the 28/2.8, 50/1.4, and 60/2.8M. Good but not great, the 180/2.8 and the 200/4.

The only one I didn’t keep is a 50/1.7.

I am thinking about buying the 28/2.0, but it is a lot of money; how does it compare to the Nikon 28/2.0 AIs?

I’ve heard a lot of good things about the Nikon 28/2, but honestly never used one – the ZF 2/28 was always around and handy. Cheaper than the CY version too, I believe, and has better coatings.

Yes, Leica. I used the Leica R 35/2 and 35/2.8; 50/1.4 and 50/2 ; 90/2 (non Apo) and 90/2.8.

The slower aperture lenses are slightly lighter, a lot less expensive and the I.Q. is better, as it should be.

Rarely stated, because many people equate price to I.Q.

Many people equate price to many things, not necessarily accurately… 🙂

I will try again. You mention two cases where fast lenses may excel. I can add a third, but perhaps most photographers don’t go there. And that is the value of a very fast lens that is also sharp and well corrected like the Otus series and many of the more exotic lenses that we find in large format, etc. And that is if you stack focus as I tend to do.

In that case, I’m not limited by a very fast, very well-corrected, and “sharp” lens. Using the razor-thin depth-of-field of such a lens, we can stack by layers whatever amount of sharp, in-focus areas we want, leaving the remainder of the image (hopefully) in lovely bokeh. I do this all the time and have for years.

However, I am always on the tripod, often in the studio (but not always), and I find it fascinating to stack focus with such lenses. I also enjoy by focus stacking the fact that such photos work against and play down the traditional photo-image tradition of having a single plane and point of focus.

I like to stack so that there are several points of focus (or the whole thing is in focus) and the eye is not so easily directed to just one point or plane, but rather is freed to range about the photo looking at what we will. I find this very freeing and enjoy not always being bound to a point and plane. Just my two cents.

But in essence aren’t you extending the effective DOF by stacking…? 😉

Yes, but in that case you could get a hardcore transition from sharp to blur.

You also get this with a highly corrected lens – a shallow or ambiguous transition is usually because the focal point of different wavelengths suffers from some dispersion, resulting in a ‘sort of in focus’ appearance spread over a deeper plane.

It can be used that way, but I’m sure you know that with focus stacking we can selectively have different areas of the photo in focus irrespective as to whether they are in the front or back. My main point is that by removing the traditional one-point/one-plane, we can free up the eye to make up its own mind where to look instead of prompting it. I find it very freeing to pick where I want to look.

I stand corrected; this makes sense to me now…

Focus stacking is often said to give us more depth-of-field (DOF), which can be true if we always move from front to back of the image when we are stacking. That’s something beginners latch on to. However, it is so much more than just putting everything more in focus.

By stacking focus, we can also have areas of the image in sharp focus, even if they are in the front, back, or middle of the image. And what I find most useful is that by stacking focus I can use very fast lenses (well-corrected) that are also sharp wide open to paint blocks or whole areas of an image in focus.

In general and traditionally, fast-focus lenses are used when we want a razor-thin depth of field with one slice in sharp focus and the rest in bokeh of one sort or another. However, by using fast, well-corrected, and sharp lenses we can (as mentioned) paint focus where we want and leave the rest to go to bokeh, which fast lenses are famous for.

By breaking away (taking a break) from the traditional one-point/one-plane of focus, the eye of the beholder is not automatically prompted or drawn to a pinpoint or plane in the image. Instead, the eye if free to roam around and assume whatever view pleases. It is kind of a new experience!

This is what I find so liberating about stacking focus, the freedom of the eye to direct itself. It is also, IMO, why stacked images have been said to be a little psychedelic. We are not used to having our eyes to point things out for themselves. It can be an adventure.

Out of curiosity, how does the stacking software put it together when there aren’t gradual transitions between each zone? I find that with a normal stack even if you miss one ‘slice’ it usually throws things into disarray and it isn’t smart enough to figure out what goes where in which order (albeit missing a piece).

There are lots of ways to stack. There are long 25-30 and very long (160) and “scientific” (hundreds) of layers, but there are also what I call short stacks. A short stack might be from 3 to 7 or so layers and photos are not taken in serial sequence from front to back. Instead, you can just make a stack out of points of interest. For example, you have a subject with five flowers. You might take a shot of each flower focusing at the very center of each and stack those. You end up with a photo with five very sharp flowers and the rest just blends in. It is very easy to do.

Or, you might take a shot of the whole scene with the lens wide open and get a field of bokeh. Then take a few shots of individual flowers at an aperture with more depth of field and stack the bunch. This type collage-stack may require more retouching to bring the different layers together.

Stacking, like DVDs and CDS, is a digital sampling technique, where by definition some data is lost while the data you want to keep is highlighted. There are many methods, but each has a specific result. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. For example, I don’t like most HDR photos, but I do like a well punctuated stack.

So, if we think of focus stacking as just having everything in focus, I (jokingly say) “Why not just take a picture.” I look at stacking more as if each photo is an impression of what I see or the world as I would like to see it (or sometimes do). Ming Thein is my favorite photographer, but my work is nothing like his (not that I could do what he does!). I kind of paint with light and like images where parts of the image are stacked and in sharp focus or micro-contrast, while other parts are bokeh or extreme dreamy bokeh. Examples of what I like can be found here that speak louder than words.

https://MichaelErlewine.smugmug.com

This makes sense – I was wondering how you’d avoid the retouching because the stacking SW tends not to know where the ‘edges’ are if it doesn’t have a sequence of frames to determine the depth map.

I absolutely can’t do what you do either – my brain is too hardwired to see DOF as a single continuous plane rather than separate ones…but now I’m going to have to try this. Thanks for the inspiration!

At one time or another I have bought all the major software that stacks focus and tried the free-ware too. For my purposes, Zerene Stacker is my software of choice. It offers two major approaches to stacking, that if combined can produce images that I like. They are called PMax and DMap. Briefly, DMap protects color and PMax protects detail. I always use Dmap first because to me “Color is King,” and then I fill-in by retouching with PMax. I find the retouching features of Zerene Stacker to be more profoundly useful than other brands, IMO.

Retouching is an art as I see it. So, I don’t avoid retouching, but work to become skilled in it. I also have tried focus-rail auto-stacking, but don’t use it often, not to mention every kind of focus rail. A lot depends on how you stack. The very best way to stack images for modern stacking software to handle (and avoid artifacts) is on the view camera by moving the rear standard. The second best method is by turning a helicoid on the lens or a lens barrel, and the worst (relatively speaking) way is to use a focus rail. I pay attention to that.

I also experiment constantly. In fact, I consider all my photography as experiments, rather than finished pieces. I have shot many hundreds of thousands of images and have yet to print out a single one. And never have I put a printed image on the walls of my home. To me, photography is not a vocation, but a passion. Although I am getting decent results these days, the process of photography has always been more important to me than the results. Perfecting the process perfects the results, IMO. In other words, the place we are going is how we travel. That idea.

I’ll give that a shot – I’ve been having good results from Helicon for what I do, but it tends to fall down if there are a lot of ‘holes’ in the subject structure.

I try to post a longer comment and am told it cannot be posted. How does this work please?

It’s showing up just fine here…?

Hi Ming,

Thirty years ago, I choose lenses mainly according to the diameter of the filter to avoid carrying duplicates and adapters, all Nikons from 28 to 135 mm in diameter 52 mm. Only the 20mm and the 180 mm were in diameter 58mm and 82 mm, but all were at f 2.8, except the 1.8/50 mm (52 mm).

In older days, I heard about a BW portrait photographer who shot in 18/24 with a lens as fast as a turtle and no more corrected than a glass of beer with “softener inside”. The size of the negative allowed him to make direct retouches with a magnifying glass before printing. The lens blurred the wrinkles and erased unwanted informations.

Your right when saying: “an image that says less is a weaker one”. It’s about context and the choice to include it or not. The focal plan will allow us to touch the quintessence of a motion blur with the beak of a sparrow in flight snapping a gnat, when both are well aligned. But what will we see from the gnat or the beak if the sparrow faces us or is slightly awry? These are two different stories with certainly a blurred background.

Our brain uses our eyes to reconstruct the set, from a detail, with a piece of depth of field as thin as it is. It also works by stacking disorderly macro filters beyond reasonable.

Paul Klee said:” The eye follows the paths that have been laid out in the work.”

Low-light, available-light, rest- light photography with fast lenses is like freezing the print in developer tray when it begins to appear, from nothing to something, trying to answer the question of the very first moment.

I think these days they try to have as many variable filter sizes as possible, and as large as possible…who’d have thought 95mm would become mainstream!

A little OOF can be useful, though: it gives us orientation in the third dimension, which is difficult in a normally two-dimensional medium. However, the problem comes when things are too blurred – your context is gone.

On Klee: I believe he was taking about structure; for story you need sequence/causality and for that you need structure. And for structure one needs to at least have a fairly good idea what you’re looking at…

You know those Sirens probably wouldn’t get me on the rocks! Very very seldom do I take a photo and wish more was out of focus! I own fast glass, but unless I’m shooting in the dark, I’m an f/8 man. Here’s pretty much the only photo I’ve taken with a fast lens wide open for creative effect that I still actually like: https://flic.kr/p/24bmSEK

I can see why. Interesting composition and the background wasn’t totally obliterated to the point of erasing the context.

I fully agree with you. One point however I would like to add: the Zuiko 45/1.2 simply is a mere joy to use . . .

I’ve also heard good things about the Panasonic 42.5/1.2, but both are enormous for M4/3!

Everything is relative in life – I have come from a D4 . . .

That’s also true!

MF lenses make Otuses look compact…my 35-90/4-5.6 normal zoom is bigger than a 70-200/2.8.

Very interesting as usual, thank you Ming. Something missing in the comparison fast / slow lenses: very often, the faster lenses will have more flare. Their front element is larger, and there are more elements with more interfaces glass / air.

True, though the larger number of elements is due to the correction requirements of faster optical designs – this can however be overcome with better internal coatings and baffles (the Otuses are a good example of this; they have a huge number of elements but also some extremely sophisticated coatings even on the edges of elements to prevent stray reflections and loss of contrast).

I forgot… the excavators look great! Never get to see more than one or two at a time in my little country…

Haha, thanks!

I agree on the concept that people do not need fast glass for a lot of subjects. However, I see a lot of amazing photographs taking by professionals and artists taken wide open with fast glass for the right subjects that are amazing. I agree that for your preferred subject that maximum depth of field is preferred but not all of us shoot this subject. It is a case of buying a tool to achieve your artist goals, versus buying expensive heavy glass that you do not need. I enjoy some fast glass for certain subjects and then wish for quality slow glass for compactness.

Depends very much on the subject, I agree – but I really can’t think of any subjects that don’t benefit from some identifiable context…

I can but that does not matter. I asked some time ago if the Hasselblad X1d could do histogram before image is taken and I think you misunderstood question as your response showed how to see it after photo is taken which is not particularly useful. I do not see anyway to see how to review before photo is taken and older reviews critiqued this but cannot believe that this is an oversight for a number of updates for those who like to expose to the right.

I also thought on one of your posts, you mentioned that you were promoting the development of the Hasselblad Xcd 80/1.9…

At least in the last FW I used (I don’t remember if this was released publicly or not) – you get an overexposure clipping warning, which is live and in the finder. This is just as useful as a histogram (perhaps more so since it doesn’t have to overlay one corner of the image) to achieve correct exposure.

Yes, I did push for development of the 80/1.9 – remember, 1.9 isn’t that fast, and medium format available light work is much more limited than smaller formats because we lack both fast lenses and any form of stabilisation; the reality is with the current generation of FF sensors, at the same resolution, you have equal high ISO performance, and possibly gain 3-4 (or more) stops of latitude because of stabilisation, without counting f1.4 lenses (vs f3.2-3.5 as is normal for MF). This puts you at a significant disadvantage out of the gate, so we had to do something to close that gap. Stabilizing a 44×33 sensor is non-trivial as the amount of ancillary circuitry etc. and the overall weight of the sensor board is about double that of FF, which in turn requires more power and limits effectiveness.

I’m very curious to see how effective the IBIS will be in the new 100mp Fuji GFX.

My guess is much better than nothing, but I don’t think we’re going to get five stops. My experience is that effectiveness decreases noticeably as sensor size increases simply because there’s much more mass to move around, often with higher precision as resolution increases. M4/3 is about a 0.5-1 stop more effective than the best APSC, which is in turn a similar factor better than FF. Realistically – 2-3 stops max?

I get the feeling I discovered Micro Four Thirds kind of late, but here is a format for which “f/1.something” strikes the magic balance between enough depth of field and subject isolation plus portability in portrait lenses. It is also the only format where you can shoot affordable lenses wide open and have good image quality. I love it!

Do you focus your wide or normal lenses to maximize depth of field or are you OK with a slightly blurred background?

Benefits of a smaller system designed from the ground up; f1.8s are definitely a sweet spot here.

DOF: depends on composition and subject…

With the developments in computational photography (e.g. the portrait mode in the iPhone X/XS/XR) one outcome is the lesser need for fast lens, or even certain large sensor cameras, in scene where background separation is needed. Rather than optical effects, the bokeh can be computed based on depth information by digital processing.

This doesn’t mean fast lens aren’t useful in certain scenarios, but they will be less practical as the number of use cases are reduced.

It doesn’t look the same – at least not yet. And there are limits to how much distance information can be collected by a small sensor or closely spaced sensor pairs – it may not be enough to differentiate between very fine textures (e.g. hair, or small gaps between subject and background) and this is generally where these systems find their limits…

Don’t know much about cameras, lenses and the like. But I do know that these are spectacular photos. You and your cameras have good eyes!

Thanks!

It’s not an either/or: even if you do go back to making [more] pictures yourself (which of course you still do), keep this blog going even if you can only devote less time to it. We’d be patient.

Perhaps missing from the discussion is the great improvement in sensors and acceptable ISO levels. The f.14’s an lower were necessary for film and early sensors to achieve one of the main objectives you highlighted, low light. But with high ISO ranges, low light takes on a new, hmmm, light. With a f2.0 or f2.8 today, all you have to do is up the ISO to keep the shutter speed acceptable in low light. [Now I realize I’ve also forgotten in-camera lens stabilization, which also changes the game a bit.] Not to mention new ranges for cropping. Cropping 35mm film leaves you with too small of an image for acceptable printing at larger sizes. But I discovered right away with the GR1 with a 28mm lens and “modern” sensor, that you could readily crop to what would be a 35mm or 50mm image size and still be able to print large enough to hang on a wall at home, certainly for a magazine or book. Then comes the Leica Q with an even larger sensor, but still at 28mm, that actually had a built in crop so you could visualize and then use 28-50mm framing, while keeping the image at 28. My home Epson Printer only prints up to 12×18 inches, but that’s still within an acceptable range of resolution at 24MP. Now we’re heading to 40 and 40 MP, and improved lenses. Needless to say, all of this just supports your conclusion that 2.0 and 2.8 or so is more than adequate, especially after taking of the low light requirement.

Whilst I do know there’s a small population that appreciates my work here, I think that’s the bit most people miss: I don’t have to do anything. I’ll do it so long as I want to, and so long as there isn’t something that is a better use of my time or more interesting. I’ve never quite been able to get used to the massive sense of entitlement exhibited by some groups online… 🙂

“Perhaps missing from the discussion is the great improvement in sensors and acceptable ISO levels.”

Good point, and to that I’d also add IBIS and OIS etc. which open up that envelope further. Not everything has to be static, and sometimes subject movement makes for interesting emphasis. What I have found – to be the subject of something I’m currently writing – is that for a given size/weight/cost budget, there seems to be a sort of plateau for image quality regardless of format; there are few exceptions to this but generally each format’s strengths and weaknesses tend to cancel out. We live in interesting times…

You have said before that you tried but Zeiss didnt listen to make smaller Otus. Its a shame really. Once I handled a Milvus 85mm on a Nikon D850 , one really must be a bodybuilder to tolerate the weight of this sort of combos. Beyond 50mm faster than f2 would be just too shallow , even at 135mm f2.8 is too shallow.

Where I enjoy fast lenses is at wider focal lengths if they are not heavy , like a fast 28mm lens wont mash your background together , it will just put a slight haze on it. Im heavily interested in leica 28 f1.4 ( size & weight being handholdable ) but the price is steep.

I was very excited when saw the Nikon Z lens line up to be f1.8 lenses. They are a little bigger than usual f1.8 lenses but the weight is still tolerable (probably a price to pay for better optics) , And was also even more astonished when read your report on the 24-70 f4. They can make a slow zoom lens this good. Maybe they can make a 28-50 f2.8 lens this good but with similar size weight ? I hope this idea passes their mind.

There’s a new Leica 28/2 also, which should bring the modern optical benefits with a bit lower price (but sadly not low).

Ironically Zeiss *did* make the smaller lenses for Sony in the Loxia series…

The 24-70 is not perfect; extended testing reveals some field curvature weaknesses especially at longer distances.

For me, more importantly, is a balance between rendering wide open or close to it, but with strong qualities stopped down, meaning I like lenses that might give up a bit in the corners wide open (excluding coma) and are say superior at say F11 with even illumination, very low flare and very low CA. Color characteristics (this is where I diverge from you regarding the Zeiss optics for FF including Loxia – just don’t care for their rendering or color) including color cast (the Milvus seems warmer in rendering to say the more recent Nikons) are yet another area where lenses can be very different, and I find I prefer Nikon qualities (and at times the Tamron look). In fact, I have a very cheap (and occasionally useful) Nikon 50 f1.8D while being quite horrible wide open, is actually excellent stopped down, and an old Tamron 90mm that seems to shine stopped down to f16+ with great color, illumination and sharpness center to corner, and no CA. Great for landscape work. More recent AFS Nikon WAs, on the other hand, continue to reflect CA even stopped down which is quite frustrating, and the 24MM f1.8 AFS is challenged in low light for certain, but it is def better than the 1.4 all around, again unless you need it wider aperture.

Leica M lenses can provide that extra quality that makes you fall in love with them, while the Hasselblad lenses are very accurate color wise if you are a “true to life” fanatic.Color contrast and greater appearance of accutance is what separates great lenses from the pack, not necessarily imaging wide open. Another quality I look for in a lens is an ability to createfine detail separation and excellent color contrast in low light (though this may be a sensor/lens relationship that makes the difference). In my own experience, there are few lenses that satisfy in this regard. But I have not tried them with the Z7 so I should allow the jury to remain sequestered.

I have seen incredible images with the Leica Noct 50 closed down which might put others to shame at similar apertures.

Clearly if you are shooting mostly landscape work, most lenses at smaller apertures should suffice, but it comes down to color and minimization of aberations which for me is key. Since few testers compare lenses at say F11 (and there may no material reason to do so), I on the other hand would appreciate finding lenses that shine stopped down but are still very good wide open.

As to use of wider aperture for creativity, I would say it all depends. Another challenge for me even with a WA shooting at f16, I may still not get everything in focus due to having a strong foreground close to the lens, even after using hyperfocal focusing. And while focus stacking may be the current fad, I sure would prefer to get the image on only one take (so to speak). Call me lazy or old, and not in love with most TS lenses (havn’t used the 19mm yet).

Nice urban landscapes btw.

Actually, extreme corners that improve on stopping down (whether resolution or field curvature) aren’t that much of a penalty for fast lenses since those areas are unlikely to be in focus at large apertures anyway (but as you say, coma is another thing – it means you can’t have peripheral subjects at all).

As for the 50 Not, it is a strong performer stopped down, but seems to defeat the point of paying a silly amount of money extra over the 1.4 (or even 2.5) if you are going to use it this way – or even if you’re going to shoot lower than f1.4 (or 2.5) most of the time, for that matter. I don’t see any practical difference in performance between the 0.95 stopped down and the 1.4 stopped down; if anything, the 1.4 may be slightly better – I have the feeling it controls lateral and longitudinal CA a bit better than the 0.95.

f16 and WA: if pushed, I’d let the background run OOF slightly; I find this helps with apparent separation and spatial cues in the image…

I’m the opposite – I much prefer the draw of Zeiss lenses to most Nikons and especially Leica, both of which I find warmer (particularly Leica). Don’t get me wrong, I love my Nikon lenses, but I Zeiss is across the board (all else being equal) my favorite in terms of color rendering, microcontrast, macrocontrast, and their ability to cleanly slice planes of focus.

Ironically, you mention Tamron – one of the reasons I switched from the Nikon 85mm 1.8G (a fantastic lens especially for the price) to the Tamron SP 85 1.8 is because it had a much more “Zeiss like” rendering. Cooler colors, more microcontrast, and better bokeh for portraits.

I haven’t used Hasselblad much, but my time with an X1D and a couple of the primes has shown me that Hasselblad definitely has the best color out there – which I’m sure is a combination of lens and sensor. I wish I could get a camera that produces colors like that in a Fuji GFX body (the X1D had too many issues for me to seriously consider it, especially for the price). Hasselblad does have an excellent UI though. My favorite cameras to use in terms of simplicity of operation have been Hasselblad X1D and Leica SL.

Have you tried 35mm and 50mm nikon Z lenses ? how are they ?

I used to chase fast lenses and shallow DOF like all beginning photographers. Now I’m content with high quality 1.8 primes for portraits – like my Tamron SP 85 1.8, which I slightly prefer over the Nikkor 85 1.8G, it has better bokeh (the Nikkor has bad cat’s eye), is just as sharp if not more so, and has VC. I just picked up a good copy (after three samples) of the 24-120 f/4 VR (for $300!) as a general “walk around” lens. So far I am very impressed with it and the extra reach over a 24-70 or even a 24-105 is incredibly nice, especially for landscapes.

Next I’m looking to pick up a Zeiss ZF.2 135mm or Milvus 135 for portraits and landscapes, however I may get a Zeiss C/Y 135mm and do the Leitax adaptation.

And, unlike every Sigma Art lens I’ve used, the Tamron SP lenses work perfectly with all focus points, center or otherwise. My 85mm required zero calibration on my D810, which is rare for any lens. The 35mm and 50mm Art lenses I tried were terrible with anything other than the center focus point. I wish Tamron would make some shorter and longer lenses, right now all they have are 35, 45, and 85 (as far as primes are concerned).

The Z cameras are an excellent opportunity for Nikon to do something about both portability and IQ with smaller, lighter lenses that don’t need VR. I still have an old 20mm f/2.8, an old 28mm f/2.8, and an old 105mm f/2.5 in my Nikkor AI-s lenses. If Nikon made them in Z mounts I will bet there will be buyers.

They’re doing this with f1.8, but those lenses are still large; hopefully we’ll see some gains as we go wider with non-retrofocal designs or longer, with collapsible ones…

I really believe f2,8 and slower is 99% of what I need. But I noted two problems:

1) Faster lenses closed to f2,8 are often sharper and show less vignetting than genuine f2,8 lenses.

2) Unfortunately SLRs autofocus at their max aperture. Unfortunately this is regularly their poorest aperture yielding considerable focus scatter. why can’t they focus at f2,8 on demand?

An f2,8 lens with perfect open aperture would be my dream. Somehow they are hardly available.

1) Definitely; stopping down eliminates the edges, which are the least corrected parts of the image circle.

2) Mirrorless can focus stopped down, but the range of tolerance for ‘in focus’ increases; you won’t get focus shift, but you might hit system limits especially at longer distances.

They say to get a perfect f2.8 lens buy a f2 or f1.4 one and stop it down…which is pretty much the design philosophy behind the Otuses; they have much larger image circles than required, taking only the highly corrected centre portion – even at f1.4. F2.8 is also not sexy for the marketing department, unless it’s a zoom…

“They say to get a perfect f2.8 lens buy a f2 or f1.4 one and stop it down…”

Yes, but why do I have to live with the weight penalty? Why can’t they go straight to the requested f 2,8 aperture and deliver that as an outstanding aperture. I would be willing to pay for that!

Sigma went a long way in that direction with their Merrills. Outstanding glas; f2,8. Good sensor (at ASA 100). The putoff is the dismal raw converter (crashes etc.; very – did I say veeeerry slow; When you do get results, they are fantastic). The Ricoh GR comes to mind as well: a very sharp lens at f2,8….

I’d rather have perfect period; why pay for an aperture you won’t use (or use with regret?) :p

An additional thought: depth-of-field is really a misnomer!

Theoretically, there is always exactly one, infinitesimally-thin, plane of focus. You cannot actually change the “depth” of focus; you only change the size of the circles of confusion.

Unless, of course, you’re employing Scheimpflug… 🙂

That’s true, and the rest is a transition between blur and apparently “sharp” for a given resolving power; it diminishes with increasing resolution, but that’s another article for another day…

Nice. But I’m still hooked on fast lenses! 🙂

It does bring up an interesting conundrum, though.

Back in my film days, it seems like we were always looking for ways to increase depth-of-field, using different shooting techniques, different subject arrangement, different lighting, etc.

Fast forward a couple decades, and the Fool Frame enthusiasts are pounding on “crop sensors” for their alleged failure to do subject isolation. And yet, a couple decades ago, these same people (if they were shooting then) were probably trying to increase DoF!

Bottom line: as I taught my photography students, DoF is just a tool. Use it wisely and purposefully to accomplish your goal, whether that be telling a story or isolating a subject.

The only reason I can think of for this is a lack of conviction/clarity in their own work: if you know what you want to produce, you pick your tools accordingly and just go out and do it. Why all the angst and debate?

Fast lenses for slow light, slow lenses for fast light.

Depends when you run out of shutter speed, sensitivity or tolerance for subject motion…

If I’m out all day on a once in a lifetime shoot in some remote place I want the lightest possible load and I would rather carry a 250g lens than a 1000g lens. However in my experience often the faster heavier and more expensive lens is also the better lens at f5.6 and f8 for edge to edge sharpness. Maybe the difference is small but you don’t want the lens to be the weak link in the result because you left it behind! I wonder if zeiss had made a stop slower wide or standard Otus how much smaller and lighter it would be. Zeiss make a 28mm and 35mm and standard that are the biggest and heaviest lenses ever but arguably the best ever as well. For me the solution is to carry the minimum and the best and just concentrate on the image. One camera and one or two lenses and tripod, hopefully under 4kgs total. Incidentally I recently bought a very old 55mm AIS Micro Nikkor for next to nothing and was staggered by how sharp it is and it only weighs 200g or so!

True: what you’re describing is a consequence of economics rather than lens design, though. People buying smaller/slower lenses also tend to be on a budget, so there are optical and other compromises. Slower lenses are actually much easier to correct and make high performance. Pricing aside, for performance consistency vs size vs speed – look at the Leica lenses; in 50mm we have f0.95, f1.4, f2, f2.5, f2.8 – pick what you need by maximum light gathering ability (or affordability) rather than performance.

Using the leica 50 s as an example plays to my experience . While I agree with your overall conclusions ….there are exceptions even in within the Leica M . My pick has always been the Leica M 50/1.4 asph . It has an exception balance between size and performance . The ability to have a fast normal lens can be critical in street shooting to deal with situations where (1) your composition can benefit from separation of the subject from the background or (2) you need the speed to be able to retain and adequate shutter speed /ISO selection . (E.Puts had a excellent analysis of the OTUS 55/1.4 and compared it with etc 50 M Lux . ) .

The other exception has been the Leica M 50/2 APO …this lens requires a level of precision beyond a practical cost objective . Yes they can make it but at $7-8K its very costly . (and it is very hard to hold the production tolerances required ). Yet its very small and very high performance .

Another aspect that comes to mind having used and selected from all the Leica and Zeiss alternatives …would be the aesthetic produced . As you mentioned the bokeh ( both blurring of out of focus as well as the roll off from the plan of focus ). This would be a long discussion but suffice to say ..”the look “ produced matters . And it is most apparent at wise apertures (easier to see) …the differences show up at smaller apertures as well .

So while your point of view is well respected ….faster isn t always better ……depending on (1) what type of images you are trying to build (2) you tolerance for size and weight and (3) your price sensitivity …there can be many different conclusions .

Excellent thought provoking essay ..thank you.

I agree with your choice – I have a 50/1.4 ASPH M myself, which is the eighth one I’ve owned. There have been many duds, some sales due to system changes/ liquidity etc. but in the end I managed to get an exceptional copy, which I intend to hold on to – more so since it covers both the X1D’s sensor and can be adapted to pretty much any mirrorless camera.

As for shutter speed vs aperture – there’s also a tradeoff with focusing accuracy and missing the shot because DOF is too shallow, but in certain situations it can be rewarding if used well (cinematic-style photography, for instance).

Not going to start a discussion on quality of OOF areas – that’s a whole separate discussion, and full of subjectivity. 😉

A good example of the use of a faster lens to allow for either a faster shutter speed or lower ISO …would be found in the harbor photo on the HB description of the new 80/1.9 lens for the X1D . (sure you are familiar with it ). In this situation ..the subject is at a distance and while DOF could be important ..its not the primary concern . Here the photographer would be up against ISO 3200-6400 to retain an hand holdable shutter speed ….having a stop and half more EV makes it possible .

The point on aesthetic is more than strictly an subjective evaluation of bokeh . An OTUS for example has class leading micro contrast without relying on strong macro contrast . This allows the photographer to establish his personal aesthetic across a broad range of possibilities . My only point is that these lenses will render a scene differently and you might select one or a group for different purposes .

Yes it would be great if the lens designers would build class leading lenses with f2.8 apertures ….looking for the highest quality while maintaining a smaller size and weight .

I’m well aware of the XCD 80/1.9’s properties – I started that project, and for the specific objective of extending the shooting envelope of MF. 😉

The Otuses render a specific way but at all apertures – this bit is important. Arguably they could build the same properties into a smaller/slower lens, but they chose not to…

Great examples, and all striking images. I would go a little further, and say that apart from the light advantage and background differentiation you mention, along with obvious soft bokeh for portraits, in the majority of cases for most people larger DOF is an advantage. Sometimes it seems that razor-thin DOF becomes a bit of a status fetish like fast cars and branded fashion.

Definitely a status fetish; it can actually also be unflattering for a portrait as objects in front of and behind the focal plane will appear to expand/spread since their image does not converge; this can make facial features (especially noses) appear disproportionately large.

Very insightful as usual, Ming.

This process is something most photographers go through, I think. When I started out, picking a camera/lens combo pretty much amounted to, “How can I get the thinnest depth of field for the least amount of money?”. So I have a few thousand old photos mostly of old girlfriends with (usually) razor sharp focus and completely blown out backgrounds. Same for still lifes or anything else where I was able to get close enough to blow out the background. Think food photography where the very front tip of the first french fry on the plate is in perfect focus, and the rest might as well be mashed potatoes :p

As I’ve grown (hopefully!) as a photographer, I’ve become more interested in using the *correct* depth of field for what I’m hoping to convey, instead of simply going for the maximum. While I still love my 35mm f/1.4 and 85mm f/1.8 and other fast lenses, I find myself stopping down to f/2.8, f/4.0 and f/5.6 for a lot of portraits, and much further for photography that’s less people-focused. Context is hugely important to make an image speak to a broader audience, and often makes the difference between, “Oooh, that’s pretty!” and, “Oh wow, that’s an incredible photograph that actually tells a story!”. One of my favorite early photographs was shot with an APS-C kit zoom (the Nikon 18-140) wide open – at something like 100mm f/8 FF-equivalent… The only reason the photo turned out so good was the fact that the kit lens and smaller sensor limited my ability to blow out the background any further, forcing me to keep sufficient context in the photo. If I’d had an FF body and, say, a 24-120 f/4 at the time, I’m sure the image would have been significantly less interesting.

There’s a time and a place for fast lenses – Full body portrait? Maybe use f/2 to get a little background separation at 35mm, while still keeping any important background elements sufficiently recognizable. Framing only the upper body with that same lens? You may want to stop down to f/4 or f/5.6 for that same effect. The tricky part is recognizing and learning WHEN stopping down benefits the image in general.

These days I tend to work with as much DOF as possible, unless I need more light gathering – and even then with the current generation of sensors, that’s rarely faster than f4. My back thanks me, too! 🙂

Ming,

The internet has exponentially educated us about lenses, and as a result the reputations of many lenses is now firmly ingrained with photographers.

The reality of such lenses becomes secondary to their reputation, and prices reflect this. The opposite is also true, some real gems are available at an extremely good price, their reputation has not spread like wild fire through the forums and internet communities. Optics can provide a lifetime of joy if understood, the lack there of is often times evident on many forums and the endless promotions sponsored by the manufacturers.

Sssh! We shouldn’t talk about things like the C/Y 85/2.8 MMG, the Voigtlander 180/4 APO-Lanthar, Hasselblad Superachromats etc… 😉

Couldn’t agree more, Ming, with the theme of your article. I have two Otus lenses – the w/angle and the standard – and I love them for what they do. But I also have other gear, which probably gets far more use, because I am using it as a “late adopter” to learn more and explore about what I can do in digital that I was unable to do in analogue – so the other gear is extremely important to me, too.

The Otus basically does anything you want of it, at any distance and aperture. Few lenses have this kind of consistency. But most of the time it isn’t the shallow DOF that’s attractive – it’s the separation due to high correction/convergence of light rays even when stopped down, or close to infinity. In my mind that’s what makes them such versatile and attractive lenses…and yes, too bad about the weight.

Hi MT !

This was a legendary article .

I m beginning to notice that you r one of a rare disappearing breed of photographers who actually what matters most : the image .

And you also value the cost of achieving great image at low cost so that one can make money in a photography market where even smartphone photographer s are creating incredible images .

That said , your advise that one must master light and may I add lighting including mixing sources , colours etc and other timeless techniques like the exposure , is the mantra for survival and growth .

Of course good equipment helps but great is always the enemy of the good .

Thank you so much for this morning enlightenment .

Abhijeet from New Delhi , India

My pleasure. And yes, with equipment sensationalism ruling the day and distracting impressionable minds, eventually I’ll stop writing too – there won’t be a need or point anymore. I’ll just go back to making pictures for myself, which is really what photography should be about! 🙂

Sad to hear that but it’s true .

The digital world is killing humanity .Can you imagine there’s an App now called Arsenal . It’s got Kickstarter funding for God sakes !! That app will decide everything for the photographer like exposure , shutter speed etc …it’s what they call Artificial INTELLIGENCE BASED app ….

And this is just the beginning of the conquest of humans . The final assault on your humanity . What does one expect 5 or 10 years down the lane ?

While humans are busy arguing whether eye auto focus is better on Sony or the Z System , the AI will render the very being human redundant .

Ming you r right .

We will have to return to that happy corner in our lives and keep creating till creativity matters to humanity

A robot will write the first film script now . Robots are already serving in restaurants , cooking and fighting wars .

What are humans going to do ? AI will drive cars .

No human knows what s happening inside the huge computers that control every aspect of our lives including sex .

It’s actually time humans stand up and reject computers and their concontrol over our lives and what makes us human

Is it a coincidence that since Microsoft Word came we haven’t had our Shakespeare or Shelly

Digital photography will never allow humans to scale the heights of photographers of the 40 s & 50 s ….

It’s much more serious .

But yes Ming I share your sentiments.

Any task that can be automated eventually will. By its very nature creativity cannot…

Laziness in consumers makes them vote with their wallets without thinking – in a way, it makes for less competition for those of us who remain, but it also makes life harder as we are usually judged/selected/paid by those who happen to fall into the former category, too.

“… you lose a lot of the storytelling context …” I absolutely agree. For me, getting good context is something that makes photography difficult – and makes it rewarding when I succeed. In addition to losing the story, lots of out of focus area in photographs tends to bring back less than pleasant memories of the time I spent working for eye surgeons. Same with heavy vignetting.

Eye surgeons, haha!

Lighting does much more for isolation than shallow DOF, and you can use it past hyperlocal 🙂

You have a remarkable knack for articulating – and answering – ongoing debates that I have with myself. Thank you for ending this one!

I think it’s because we probably all have the same debates, but I might have had the struggles for longer 🙂