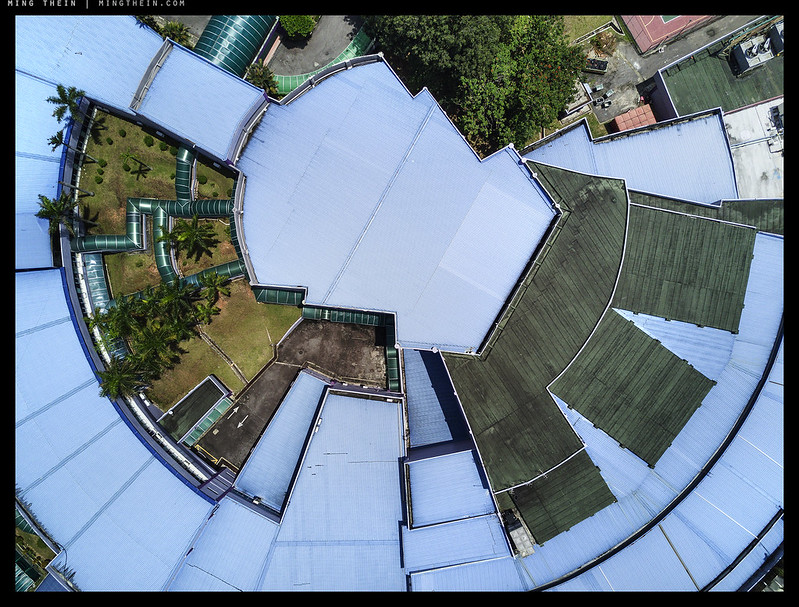

More months, more flying. I’ve come to believe that real appeal of aerial photography lies solely in one thing: the ability to see familiar places or objects or classes of objects from a drastically and otherwise physically inaccessible perspective. An image shot from a slightly elevated level with gimbal only slightly down is not that different to standing on a hill or building; an image shot from some altitude and entirely top down is at the other end of the scale. Most of the really interesting drone images I’ve seen or personally captured seem to fall into the latter category. We are coming dangerously close to the automated and the formulaic, here. Or are we?

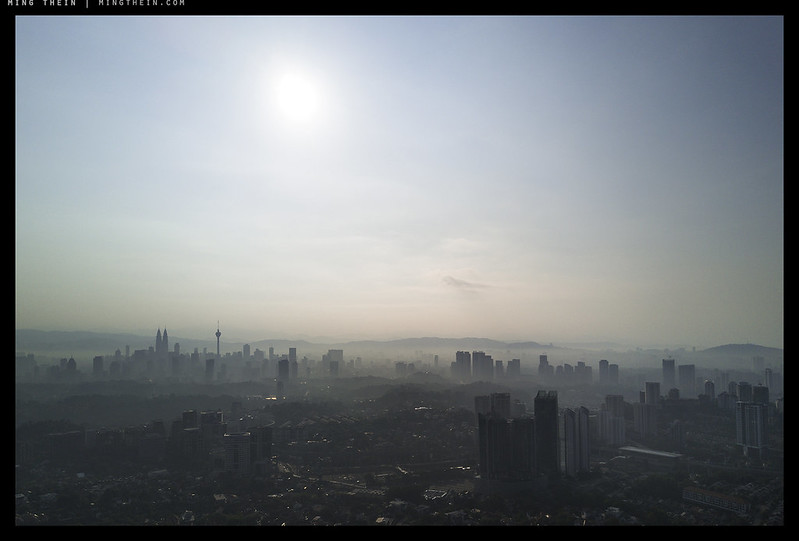

In some ways, shooting with a drone forces you to completely re-examine one’s photographic fundamentals. Interesting light is a given, though remember this is subject specific: whilst long shadows can cast interesting silhouettes, flatter, lower-contrast light on certain subjects can work too – it all depends on the subject and creative intention. Foliage, for instance, seems to work better with diffuse and lower contrast; otherwise the spatial frequency of leaves and other reflecting elements can be too high and make the overall image just look gritty. There is a certain amount of exposure control, but limitations in terms of what’s interesting perspective-wise; drones with longer tele lenses aren’t widespread yet (other than interchangeable lens options on the Inspire 2) mainly because of weight and the necessity of having a second camera for the pilot; so in practical terms, you’re limited to wide. That’s somewhere in the 24-28mm range. Anything more than 45deg gimbal-up to the horizontal results in fairly ordinary perspectives; we’re back to relying on extraordinary light to carry the shot. Anything more than 45deg down starts to get interesting, but we face a new problem: one of orientation.

I’ve found that if you’re not very careful establishing which direction is the implied ‘up’, you can land up producing a very disorienting image. There’s no inherent reference a lot of the time – in the best case, you have shadow direction suggesting bottom and highlight edges suggesting top – however, even this often fails as soon as surfaces become three dimensional and subject elements get hidden in shadows cast by other things. It doesn’t help that moderate wide angle geometric distortion inevitably results in some stretching towards the edges of the frame, too – which further means that one has to be careful putting dominant objects at the edge of the frame, as they will stretch and perhaps draw attention where you don’t want them to. Conventional ideas of composing with strong foreground anchors when shooting with a drone are somewhat moot as you’re never really close enough to anything for the ‘dramatic wide look’; the best you’re going to do is with a large structure and some converging lines.

Speaking of converging lines: for some odd reason, any divergence from references – e.g. edge of frame, horizon, road grid etc. – becomes very obvious, and care needs to be taken to position the camera carefully. This is not so easy when the aircraft itself is often moving slightly, and positioning cannot be absolute. It’s compounded by wide lenses that magnify any misalignment. The only solution I’ve found is to simply back up a bit and give yourself adequate room for correction afterwards. It also makes me wish for a larger sensor for more processing altitude and resolution; right now we have to make every pixel count because there are only 12 million of them.

I actually think that a lot of the magic of a drone is lost when used for only stills: the main draws remain change of perspective and the ability to look straight down without seeing the support. For video, the draw is something else: the ability to move in an almost unlimited path around and object and in doing so, provide the audience with the illusion of being able to move free of constraints. This is uniquely differentiated from our normal daily experience since we generally only move in one plane, and even then only within defined paths.

Whilst it’s quite a lot of effort to plan, shoot and edit a video every time you go out, the new DJI Goggles are quite another experience entirely. Two 1080P screens (one for each eye) with adjustable interocular distance and diopter provide a remarkably immersive experience, especially if viewed with no flight data overlaid (not recommended!). Otherwise, it’s possible to fly off the controller as normal, but give the goggles to somebody else to experience. Is it better than looking at your iPhone screen to fly? Yes. Is there any way to present the experience online? Unfortunately, not. Stereoscopic stills would be nice, but there’s probably not going to be much of an effect with typical aerial subject distances. So, for us stills shooters – a large print or screen still reigns. But it would still be nice to have a longer lens sometimes.

In the meantime, I leave you with my adventures from around the neighbourhood – the Mavic accompanied me for its first international trip a little while back as a reconnaissance drone for quick scouting before setting up big brother M600 and H6D-100c payload, and images from that trip will follow in due course. For the stills photographer, I think this is actually the strength of the smaller drones: convenience and size meaning that you can easily see whether it’s worth setting up and sending up the big guns; whilst stills quality is very good given the 1/2.3″ sensor size, there are still of course serious output limitations. Don’t be surprised if there’s a larger aircraft in my near future… MT

The DJI Mavic is available here from B&H, Amazon or DJI directly. As are the FPV goggles (B&H, Amazon, DJI). More information can be found on the DJI website.

__________________

Visit the Teaching Store to up your photographic game – including workshop videos, and the individual Email School of Photography. You can also support the site by purchasing from B&H and Amazon – thanks!

We are also on Facebook and there is a curated reader Flickr pool.

Images and content copyright Ming Thein | mingthein.com 2012 onwards. All rights reserved

Great shots! How a drone should be used. Drones for the use of making film and photography is the only positive thing to take from the proliferation of this technology. Keep up the great work!

For me, the stills are most successful when there is a degree of abstraction, looking straight down tends to deliver this more often due to the absence of any horizon line, the flat image plane and ambiguity in the subject scale can also add to this.

Thanks for the post Ming!

Love the first photography 🙂

Thanks.

Beautiful!

Thanks.

I’ve been lurking from time to time on your web site and generally enjoy your posts. Not this time, however, as in my opinion drones are a plague and a scourge, not to say downright dangerous at times. They disturb the peace with their dreadful noise and there have been too many reports of near misses at airports – sooner or later some idiot with a drone is going to bring down an aeroplane, just like those other (or possibly the same) idiots who shine lasers at aeroplanes. I was at Ronchamp in France recently enjoying the wonderful Le Corbusier church and the whole experience was spoilt by the presence of a drone, like a plague of wasps buzzing around everywhere. No, please do not use drones. They may give you pleasure, but they disturb everyone else greatly.

Thanks for your opinion.

I have to say I wholeheartedly agree with Chris. Drones are a plague for normal visitors of a place because of the noise and sight, and in particular, drones are a plague for ‘conventional’ photographers: At certain places you always have two to three drones within your frame. This for me was recently the case when visiting the waterfall of Rio Celeste in Tenorio National Park, Costa Rica. People using drones at such places in the presence of other visitors are an excellent example of selfishness, if not to say rudeness and ‘putting me first’, showing a pronounced ‘I don’t give a f…’ attitude.

I’m not advocating a ban of drones entirely, but please, people, be more considerate.

And in addition to that – as you, Ming, write yourself -, the only successful drone images that I’ve seen up to now all work because of the graphic nature you achieve by photographing top down, and this is getting boring quite quickly.

I don’t fly them with other people in the immediate vicinity for simple reasons of safety – I don’t think there’s a problem if common courtesy prevails, but frankly the same thing applies with the hoardes of inconsiderate ‘normal’ photographer tourists too…

Please don’t get me wrong, Ming, my comment wasn’t directed towards you – it was a general comment based on what I observed in the past. Of course, there is all kinds of rudeness in connection with photography in general not just when working with drones. Somehow some people think using a camera gives them the right to whatever. I remember having once watched a video showing a really famous street photographer (dead for quite some time already, can’t remember for sure who it was so I don’t want to spread bad rumours) at work in the streets of NYC – this guy was really so unbelievably obtrusive… easily topped the rudeness of most drone pilots 😉

Bruce Gilden? 😉

I understand your point, but blanket statements can be a little dangerous… 🙂

Remember him again: Garry Winogrand. Bruce Gilden’s not dead, is he?

Bruce Gilden – whose work I dislike – is still alive. Winogrand – whose work I revere – was Bronx born and bread (like the U.S. prez) – was pretty much in people’s faces. Still, he was only bothering a few people at a time. And was taking personal risks. He was close to them but they were to him too. He sure wasn’t skulking around in the shadows. FWIW, he preferred 28mm lenses. Drone operators are anonymous and potentially bother a lot of people. Btw, there’s a great New Yorker piece Burtynsky and what’s involved in his drone photography. http://bit.ly/2vQEQbI

Well, that certsinly is a matter of taste. Some of the people photographed by Winogrand in said video didn’t seem too amused. But as the sheer number of people bothered at the same time goes, you’re probably right.

Winograd was also famous for never looking at his film 😛

He was the guy with like 35,000 undeveloped film rolls, right? Well, he seemed to have been more interested in the photographic process than in photography itself, maybe? I don’t know whether it’s true but I’ve heard there are even people who are more interested in photographic equipment than in photography 😉

Yes, that’s the one. And equipment >>> photography? Nah! Hahaha!

Not quite accurate. He would leave his film undeveloped for months and then review. Recommended the same to his students. He appeared to become pretty manic later in life and left a very large number of undeveloped rolls (as did Vivien Meier). He produced a wonderful body of work. As for equipment – Leica M4 and 35 and 28mm lenses, so he didn’t have G.A.S.

Quote from Wikipedia: “At the time of his death his late work remained largely unprocessed, with about 2,500 rolls of undeveloped film, 6,500 rolls of developed but not proofed exposures, and about 3,000 rolls only realized as far as contact sheets being made.[8] In total he left nearly 300,000 unedited images.” Okay, so it wasn’t 35,000 rolls of film, I may have remembered the number of images instead. Why exactly did he recommend not reviewing images near-term? What I do is, I systematically look at images again after some period of time, also repeatingly, to become a bit less dependent of the concrete circumstances under which I took them. So, if the reason was something like that, I could see that.

Never said he had GAS 🙂 And I love the process of photographing myself.

Skillfully done as always, and I can well imagine how much effort went into getting these images!

Of course your career is based on pushing technical boundaries, but from an artistic point of view, there’s the danger that these can look like CGIs or Google Earth screen grabs. You know how to polish up a composition better than anyone, but just be careful it doesn’t look like something grabbed from a computer game.

0051 and 0033 I really like, and they’re all great shots as they always are with you.

Thanks, but there’s a rather big difference to google earth…

Not disputing that! I suspect I’d probably like them more if I saw a decent print, but at a glance they can put one in mind of more quotidian imagery. Certainly salute your skill and efforts in getting the images though, it must’ve taken a lot of time and hard work.

Just patience in waiting for the right weather and opportunity…

What really cool shots. We haven’t figured out how to take pictures on the drone we received.

Thanks. If it’s a DJI drone there’s a toggle slider on the app to switch between stills and video. Others…the manual may help :p

Ha. You are so right. I should just look it up. It must be on the drone itself as there is no app.

Setting up the parameters for stills is fairly simple, I think, but setting it up for video is much more complex: Format, resolution, shutter speed, ND filters ….Have you comcluded on an optimal set-up for cinematic video on the Mavic Pro?

Maximum everything for quality, keep the shutter speed high if you want motion smooth…

number one and two do it for me .Great pics

Great post! Thank you.

Thanks